Letter from the President, 1972-1976

Prologue

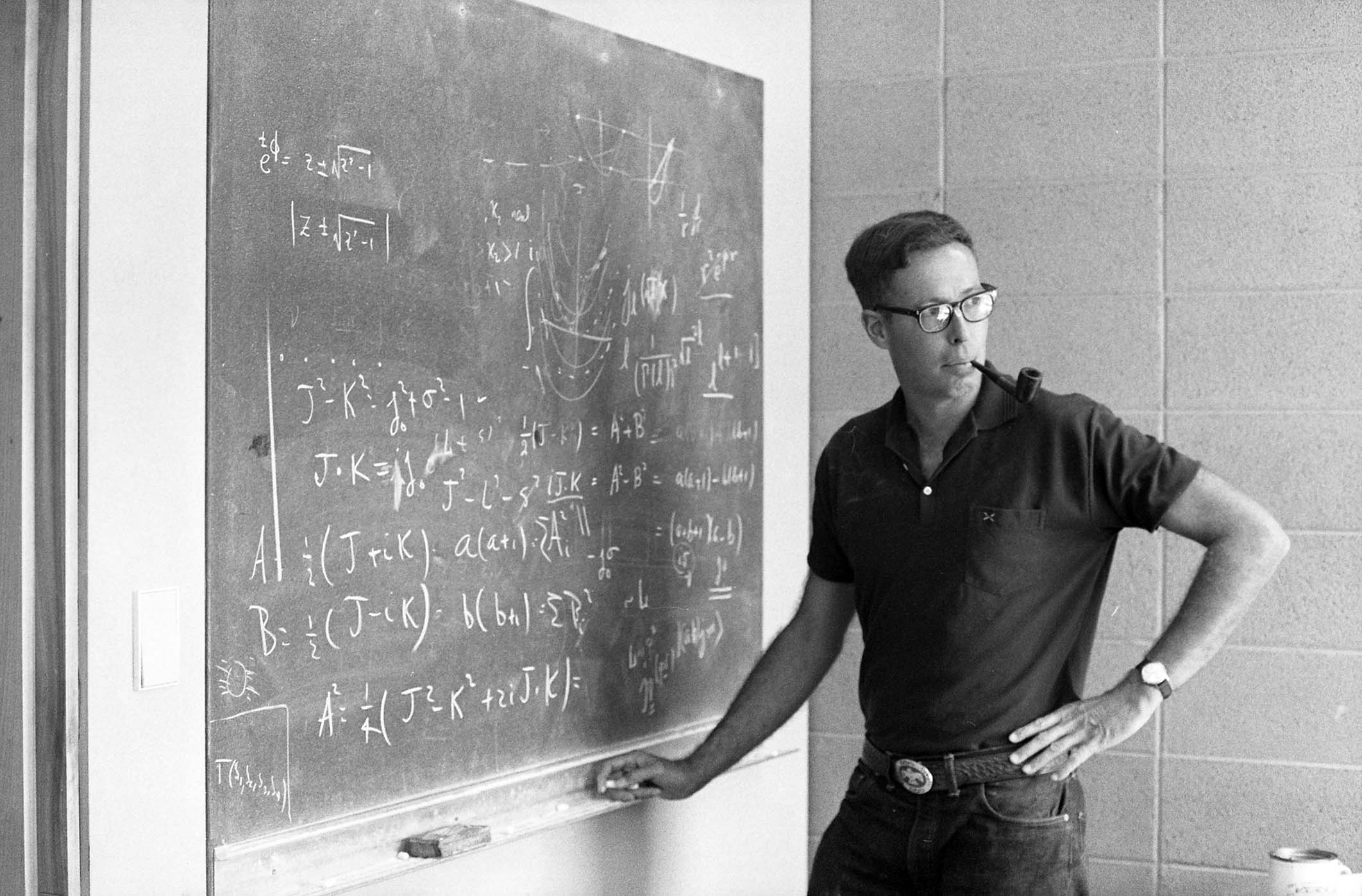

I will start somewhat before the beginning of my term as President to make clear the rapid changes that were taking place in the Physics Center through the transition period, and their influence on the subsequent development of the Center. The Physics Center was incorporated as an independent non–profit Colorado corporation in 1968. Its earlier operations from 1962 through 1967 as a unit of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies (AIHS or Institute) had been handled rather informally, initially by George Stranahan, Michael Cohen, and Robert Craig, and later by a small group, with George acting essentially as President, and Mike as Treasurer, and several of us as an informal executive committee concerned with policy questions, the selection of participants, and fund raising (M. Baranger, M. Cohen, L. Durand, D. Fivel, P. Kaus, G. Stranahan). [Notes 1 & 2]

This structure was formalized with the incorporation of the Center. This change, though initiated by the AIHS was probably inevitable given the increasing size of the program and the growing complexity of the operations. With incorporation, I became Chair of the Executive Committee of the Trustees, a position I held into 1976 when I retired as President. The Executive Committee played a steadily increasing role in the operations of the Center, especially as George’s interests began to shift elsewhere. There were several major themes in these activities as described below that carried over to later years, especially fundraising, facilities, the nature of the program, and the mode of operation.

Program Support

The Center’s operations had originally been supported in 1962–66 by grants from the Office of Naval Research, IBM, and the Needmor Foundation, and a National Science Foundation grant of $5,000 for the library, split over 1963-65. The Sloan Foundation provided support at $10,000 a year for 1964–68, and a staff grant for $20,000 for 1969, but a continuing grant, though approved by the Sloan Executive Committee, was ultimately canceled by the Sloan Board. The funding situation had therefore become critical by the late 1960s. Foundations preferred to support new initiatives rather than continuing programs, and corporate support was limited. A very welcome contribution was the gift of $5,000 by Hans Bethe from his 1967 Nobel Prize, supplemented by a later gift in 1968 for our new endowment fund.

Regular federal support proved to be very difficult to obtain. The Center did not fit into the usual categories for support by the National Science Foundation (NSF) or the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). Wayne Gruner at the NSF, when asked about further support when the library grant ended told me, “That was it, no more.” When I talked to Bernard Hildebrand, head of high–energy physics at the AEC, about a proposal submitted by the Executive Committee in 1967, I was told that there was “no possibility” that a proposal from the Center would be supported. [Note 3] While the Center was clearly dedicated to stimulating individual research and collaborations, we could not frame a proposal for support of our informal overall program in terms of support for specific projects related to high–energy physics.

We eventually obtained support from the NSF, but that was a long process. In 1967, David Pines invited Arnold Feinberg, a former colleague then rotating through the theoretical physics office at the NSF, to visit. Feinberg visited for two days in August, 1967, and was quite impressed with the activities at the Center (coincidentally, Murray Gell–Mann and Yuval Ne’eman happened to be in residence), but said that our “chance was ~0” of obtaining NSF support, [Note 4] and a proposal was indeed rejected [Note 5]. I later talked to Feinberg at a Rochester meeting in 1970 when our funding seemed close to running out. He said that the NSF would possibly contribute if we were going under, but that a regular grant was still unlikely.

The situation changed in 1971 when David invited Marcel Bardon, head of the NSF’s International Division, whom he had gotten to know in connection with arranging US–Soviet meetings in theoretical physics, to visit the Center. In a discussion on the lawn, Marcel told us why the earlier proposal had likely failed and how to reframe it, and said that approval was likely if we approached the NSF properly. We followed his advice, and the NSF indeed approved a $33,000 grant for 1972. Marcel attended the Center’s annual Trustees’ meeting in 1972, gave us further advice, and encouraged submission of a two–year renewal request for 1973–74. That was again successful, and NSF support has continued ever since

I would note here that the receipt of NSF support changed the way the Center operated, with particular impact on the program as discussed later.

Facilities

The Center originally had only Stranahan Hall, and its 10 offices quickly became inadequate; it was necessary very early to triple people up in offices, and to run an office annex in a nearby house. That situation changed abruptly with the construction of a new “temporary” building in 1968. Robert R. Wilson, the director of the National Accelerator Laboratory (NAL), later Fermilab, visited the Center in 1967. He really liked the informal atmosphere and the mountains, and expressed interest in holding the design studies for the NAL experimental areas at the Center with a group of about 85 high–energy experimenters and theorists. This would have the advantage for the NAL staff of being away from the pressures of accelerator construction, while giving the external study group an attractive place to meet, with access to a physics library, and to our experience in promoting informal interactions.

Ned Goldwasser, the deputy director of NAL, contacted George and me that fall. I was on the NAL Policy Advisory Committee, and the idea was discussed in a November meeting. In January, NAL told us it wanted to go ahead, with the Center to arrange the housing and provide facilities in return for appropriate fees. George called me in January to get my opinion and discuss the possibility of building a new building. He worked out the details with the AIHS and the City of Aspen’s nontrivial tasks – and backed the construction costs (ultimately repaid from the NAL and other rentals). The new building, a bare wooden shell designed by the eminent Aspen architect Fritz Benedict, was built in ~6 weeks in the spring of 1968.

Hilbert Hall (named for a poster of Hilbert that George put up in the lobby) was used for the NAL design studies in the summers of 1968 and 1969. It was rented to the Aspen school system for use by K, 1, 2 classes in the winter of 1969–70, with two wings partially winterized, and to the Aspen Community School in 1970–71 and 1971–2. Thereafter, it was used only by the Center. The NAL connection persisted: we hosted NAL Program Committee meetings, formally and informally, for a number of years. Bob Wilson served as a Trustee of the Center for the period 1969–75, and as Chair of the Board for 1986–89, succeeded by Leon Lederman, director of Fermilab (the renamed NAL), for 1989–92.

Size of the Program

The Center had full use of Hilbert Hall from 1970 on, and could expand its program while eliminating the tripling of offices in Stranahan Hall and the use of an office annex in various nearby houses. The optimal size of the program became a subject of fierce debate given the tension between desire to preserve the informality of the program and the resulting chance for interactions among people in different fields that characterized the early years, and the rapidly increasing demand for participation that followed the wide exposure of the Center generated by the NAL summer studies and other special programs. This debate recurred essentially every year for a number of years. It was initially decided to increase the size of the physics program to about 45 participants at a time – still very controversial for some who remembered the intimacy of the first years (42 participants total the first summer) – and the Center therefore used only two wings of Hilbert. The third wing was reserved for special programs such as a study on international aspects of environmental problems sponsored by the AIHS (1971–2); the rather contentious summary meeting of the Astronomy Decadal Survey Committee (1971) where it was decided to pursue agency–supported national facilities such as the Very Large (radio) Array as the top priorities; the summer meetings of the NAL Program Committee (1970–72) on the first experiments at the new 200 GeV accelerator; and an astrophysics workshop on The Early History of the Universe (1972) supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

The size of the program had increased to ~55 by 1972, with the Farny house then used as an annex for some special programs. Any further increase in size would again lead to overcrowding, and discussion was started on the possibility of constructing a new building. First, however, the status of Hilbert as a “temporary” building, originally to have been removed after the NAL summer studies, had to be resolved. The AIHS agreed to our continued use of Hilbert, but proposed moving it to a site where Smart Hall now stands. This move was turned down by the City of Aspen, and other developments discussed later left the whole question of its status up in the air for several years.

Governance/Operations of the Center

When the Center incorporated in 1968, the members of the original executive committee, plus our larger advisory group, became the original Trustees and General Members of the corporation, sixteen in all. [Note 7] Members, Trustees, and Officers were all elected annually, and no distinction was made between Members and Trustees. This provided little flexibility for the addition of new blood as the fields of research interest at the Center changed. The original Trustees were mainly in high–energy and nuclear physics, with much less representation in condensed matter (then solid–state) physics and none in astrophysics. There was very little turnover of the original Trustees/Members for the first few years. To provide some flexibility, the Center’s Bylaws were amended in steps to increase the number of Trustees/Members, which often engendered some controversy, with the membership reaching 20 in 1971, and eventually reaching 23. This problem of bringing in new members persisted for a number of years.

The physics program of the Center was evolving rapidly, with a push into astrophysics that began in 1969 with an August working group on pulsars organized by David Pines. The first Trustees in astrophysics were added in 1972 (A. G. W. Cameron, S. Colgate, and G. Field), and a fourth (D. DeYoung) was added in 1973. The condensed matter program also developed steadily, though less formally, hampered by the relative dearth of Trustees in that area until A. Heeger was added in 1973, E. Abrahams in 1975, and P. Anderson in 1976.

Relations with the AIHS changed over the years, from the initial close connection when physicists were invited to contribute to the Institute’s core programs [Note 8] or give public lectures as part of the Institute’s lecture series (the earliest I could find was one I gave in the 1964 series; Gell–Mann, Frazer and Bernstein lectured in 1970, Bernstein and Weber in 1971), through an edgy period prior to the Center’s becoming independent (hence the gap in the lectures), and then to cordial but rather formal relations after incorporation.

A point of particular concern for the AIHS board was Hilbert Hall: the architecture, suitable for a temporary building, did not fit in with the Institute buildings, or with Stranahan, all designed by the designer Herbert Bayer, ex of the Bauhaus. Hilbert was initially visible from the Meadows complex and the Paepcke area, and was regarded as an eyesore. This aspect of the problem disappeared slowly as the trees we planted around it grew, but the status of Hilbert remained in doubt since the building, like Stranahan and our grounds, belonged formally to the Institute, with the Center having an indefinite lease at $1 per year, never billed and never paid. [Note 9]

There were clearly a number of problems to deal with when I was elected President in 1972.

The Presidential Years, 1972–76

1972

The summer of 1972 saw a number of new developments. I had handled the admissions/housing process for the second time, and demand for space was again up. We had 154 participants from 64 universities, 6 national laboratories, and 4 corporate laboratories in the physics program during the summer, plus another 35 in a newly instituted astrophysics program, with average stays of 4.6 weeks, in addition to special AIHS and NASA programs We had our first NSF grant ($33,000), justified as support for somewhat nebulous informal workshops on “critical problems in physics and astrophysics,” and the arrangements for supporting housing had to change. On the organizational side, the Nominating Committee (Durand, Pines, and Stranahan) was able to generate support for the first substantial change in the Trustees/Members, with the election of 5 new Trustees in the group of 20, adding 3 in astrophysics and 2 in high–energy physics, and dropping 4 of the original Trustees. And I was elected President, continuing as the Chair of the Executive Committee.

The immediate problem was assuring continuing NSF support. Marcel Bardon of NSF attended the July meeting (there was then only one meeting of the Trustees during the summer). He encouraged us to apply for a two–year grant renewal, and gave us further advice (somewhat indirectly), to institute formal workshops, which could be justified more easily to referees, and open up and formalize the admissions process. These involved distinct departures from what we had traditionally done. The program had been informal except for special workshops, and our programs were announced only through circulars distributed to past participants and selected people in the fields of interest so as not to be inundated with far more applicants than we could handle.

The institution of formal, organized workshops was especially controversial, but we still moved in that direction. In further discussions with Marcel, we learned that the Astronomy Section of NSF was very unlikely to provide support for our astrophysics program, but that the Theoretical Physics Section probably would. A renewal request including an astrophysics component was submitted for 1973–74 with L. Durand, D. Pines, S. Adler, and G. B. Field as the principal investigators. The workshops for 1973 dealt with several topics of great interest at the time, and give an idea of the Center’s program: Symmetry violations in nuclear physics (F. Boehm); Scaling phenomena in field theory (S. Adler); Critical phenomena in many–body systems (B. Halperin); and Gauge theories of weak interactions (L. Wolfenstein). A large part of the program was still informal. The renewal was funded at $34,500 for 1973, and at $38,500 for 1974.

The NSF grant was mostly for participant support. We could not use this as we had used our operating funds previously to directly reduce rents, but used it instead for “dislocation allowances” to participants based on 25% of the costs of their housing (75% for those without summer support). The NSF funds for direct operating expenses were limited and did not cover our costs, but overhead from special programs got us through. Given the situation, we initiated an effort to get contributions from corporations with science connections, and instituted the first registration fee for participants ($30) for the following year, 1973. The library also needed major additions to reflect the new fields we were entering, so the Executive Committee submitted a grant request to the Sloan Foundation for library support.

1973

There were still more changes in 1973. Murray Gell–Mann became Chair of the Trustees, a position he held until 1979. M. Baranger and M. L. Goldberger were elected as the first Honorary Members upon gracefully resigning as General Members/Trustees to make space. The Sloan grant requested for the library was turned down, but the Corporate Associates program got off to a good start through the efforts of Bethe and Pines, with contributions from Bell Labs, Ford, and GE. The special NASA astrophysics program continued, with a workshop in June on the physics of the interstellar medium covered by a $5,000 grant.

The library, which had been stuffed into a small room in Stranahan, was moved by the participants to an opened–up double office in Hilbert and cataloged. My wife Bernice and I invited Pat Molholt, the Astronomy librarian at the University of Wisconsin and our friend, to visit for a few days and help organize the new library. The key to the organization was the selection of relevant catalog topics and the cataloging of the collection by the physicists, with a color/shape labeling system that, according to Pat (who went on to a number of prominent positions), “could be understood by kindergarten students,” so presumably also by physicists

As part of our efforts to upgrade Hilbert in the eyes of participants, I moved the President’s office to its unfinished A wing. In a series of afternoon work parties (physicists will work for food, especially pizza), we insulated the A wing, painted the remainder of the interior and acquired some secondhand furniture for the first time, and considerably improved the Center’s grounds. Sally Hume Mencimer was the only permanent member of the staff and money was still tight, so anyone interested in improving the facilities had to pitch in. [Note 10]

Sally had been with the Center since the third summer, 1964, and was the Assistant Treasurer. After some discussions about her responsibilities and rather low salary, I suggested to the Executive Committee that we appoint her to a new position, Administrative Vice President, to better recognize her responsibilities. This was agreed to, and she was delighted by the promotion, even without a large raise.

The number of participants present at a time had reached about 72 by 1973 because of the demand, and we were again tripling offices in Stranahan and running the Farny annex and clearly needed more space. We therefore began more serious discussion about raising funds for a new building, and again applied for a variance to move Hilbert to the site preferred by the Institute to be assured of continued use.

1974

The workshop program was now established and grew, with 7 very successful workshops in 1974: Physics of galaxies (D. DeYoung); Dual resonance models (J. Schwarz); Very high energy hadronic interactions (F. Zachariasen); Physical and mathematical models of biological control mechanisms (P. Kaus), the first biophysics workshop; Unified theories of hadrons and leptons (M. Gell–Mann); Mathematical physics (A. Jaffe); and Applications of high–energy physics (R. Arnold). A planned workshop on surface physics ultimately fell through. Then, as now, the workshops were open to any participant, and with a large number of participants still not connected specifically to workshops, a real effort was made to keep the introductory talks and discussions accessible to non–experts.

Our request to the City for a variance to move Hilbert was again denied, so its long–term status remained somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, given our somewhat larger receipts from the new registration fee and the Corporate Associates, initially Bell Labs, IBM, and GE, with Argonne National Laboratory, ARCO, and Xerox added later, we proceeded to finish the interior of Hilbert over the off season, replacing the original grossly inadequate lighting; sheet rocking and painting the still unfinished offices; and expanding the tended grounds. (Hilbert was carpeted for summer, 1976.)

Fundraising for a new building was underway. We estimated a cost of $240,000 for a building with a seminar room, library, and about 10 double offices (later reduced to 5). One opportunity came through Walter Orr Roberts, head of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, who liked to spend time just visiting the Center and talking when he was in Aspen in the summer. Walter was on the board of the Max Fleischman Foundation, which was going out of business. In various conversations, he suggested to me that we might get funds from them, and suggested that I write a request, which I did. The Fundraising Committee, now with Heinz Pagels as Chair, was charged with soliciting funds more broadly.

A new problem was also becoming evident: housing costs were rising rapidly as Aspen shifted from a quiet mountain town with few paved streets to an active resort area in the summer. There were still rather few condominiums in town– the construction boom was still in its early stages– and we had been renting 55–60 houses (!) for participants. [Note 11]These were getting very expensive, and competition for rentals with other nonprofit organizations such as the Aspen Music Festival was increasing. The problem was sufficiently severe for everyone, that we talked to some of the other nonprofits about a joint approach to the real estate rental companies. I later went to a monthly lunch meeting of the local real estate group to explain our problems and ask for their help, noting that long–term rentals to responsible groups were attractive. It did not help.

By this time, the professional character of the Center was changing in response to the larger program and diversity of workshops. It was becoming less likely, for example, that one would talk in depth with a participant in a different research field and end up collaborating. However, given the larger number of people with similar interests likely to be present, and a possible forefront workshop, it became easier to make new contacts and learn about new developments in one’s own field.

The Center’s social character changed as well. The weekly physics picnics, which had moved in earlier years among a number of nearby campgrounds and wild areas, had become too large to accommodate easily in such locations, and picnics were now mostly at the confluence of the Roaring Fork and Castle Creek below the Meadows area, or occasionally at the Center itself. Our monthly parties on the Center’s patio – social occasions featuring drinks as well as food provided by the participants, and used also to promote contacts with the community – began to fade out as the ratio of eaters to cooks grew too high.

In the early 1960s, George Stranahan and I had written a hiking/climbing guide to the area, still in use, which I update occasionally, and Peter Kaus and I typically posted notices about weekend outings we would lead, usually a family hike on Saturday and a more serious climb on Sunday, and occasional backpacks with other families. I stopped doing this when what was intended as a climb up Castle Peak with a modest–sized group unexpectedly ended up with a group of 23, including many children, caught in a sudden snowstorm on the east ridge. The hiking/climbing/camping activities splintered into self–organized groups, and happily still continue. [Note 12]

The physics impact of the Center, meanwhile, had increased greatly, first with the NAL summer studies (100+ papers in 1968 alone), then with the much larger program allowed by the addition of Hilbert, and again with the formal workshops. We were recognized as having a unique character among summer physics programs. When Boris Kayser, head of Theoretical Physics at the NSF for many years, was planning a solicitation of proposals for the year–round theory institute that became the Institute for Theoretical Physics at UC–Santa Barbara, he called me during the summer for an extended conversation about how we operated, solicited workshops, selected participants, and so forth, and used us as a model. We did not consider making a proposal.

1975

The housing–cost crunch came to a head, and we decided as an experiment to rent cheaper condominiums at Snowmass for a substantial fraction of the participants. The change caused considerable unhappiness because of the remoteness of Snowmass, and its then lack of activities, and we have not done this again. However, when we returned all housing to Aspen in 1976, the average cost of rentals jumped by 33% (still, given a chance, only one participant chose the cheaper Snowmass housing that year). Interestingly, the Snowmass option has been followed in later years by a number of other physics summer study groups as Snowmass developed.

As part of our effort to promote turnover among the Trustees, while recognizing outstanding service and retaining connections, the Bylaws were amended to add the position of Honorary Trustee. Bob Craig and Robert R. Wilson were elected as the first Honorary Trustees.

Our NSF grant had been renewed, now at $43,300 ($48,500 in 1976), and the NASA astrophysics grant was $7,500 ($8,825). This was somewhat unbalanced given the proportions of participants in the two programs and the different way the awards were written, with those in the separate NASA astrophysics program getting larger dislocation allowances for shorter stays at the Center. [Note 13] It took several years to work this out, but we eventually brought all groups under the same support plan. The NSF had also decided off–season to audit our books for the first time. Our bookkeeping system at the time was a rather rudimentary single–entry system with the categories not well defined, and NSF was discomfited, but their funds could be traced adequately so we did not have a problem. During the year, I changed our fiscal year to start March 1 instead of January 1 to correspond better to our program and support timing and reduce funding overlaps between different fiscal years. This helped clarify the books, but it was not until L. M. (Mike) Simmons became Treasurer in 1979 that adequate bookkeeping was initiated.

The dominant events of 1975 concerned the proposed new building and the future of the AIHS itself, thus our future as well. Our request for support to the Fleischman Foundation was successful: we were granted $40,000, to be committed by the end of the year (we ultimately received two one–year extensions on that deadline). The Fundraising Committee had also obtained building funds from the Esther Mazor Foundation and ARCO, and was working on other corporate and foundation possibilities. During the summer, we submitted a tentative proposal to the Kresge Foundation, introduced by Elizabeth McCormick of the Rockefeller Foundation whom David Pines had gotten to know through the AIHS. She thought Kresge, which was interested in buildings and matching grants, would be a good match for us. Meanwhile, we hired Jack Walls, a local architect, to draw up the plans for what would become Bethe Hall. (When finished in 1978 in time for the July meeting, [Note 14] it was named for Bethe to honor his contributions to the Center. In 1979, Jeremy Bernstein published a three–part profile of Bethe in the New Yorker. The lead article had a sketch of Bethe by Silverman which Bernice and I bought for the new seminar room.)

At the same time, the uncertainty with respect to our relations with the AIHS increased. The Institute had proposed greatly expanding its hotel facilities at the Meadows, but was turned down by the City. The Institute property, including the Center, was zoned “specially planned,” and there was no accepted master plan. Without a resolution of this problem in sight, the Institute Trustees began negotiations with Colorado University to transfer all the Aspen property to CU. Our interests were supposed to be protected, and we (reluctantly) approved the transfer in principle at the July meeting of the Trustees. I began correspondence with CU on our needs. Fortunately for us, the AIHS–CU negotiations fell through in late 1975. The Institute then began negotiations with Denver University for a similar land transfer of the “academic core” property, again including the Center.

1976

By this time, the problem of rotation of Trustees and Members had become sufficiently awkward [Note 15] that some way of enforcing a regular renewal of the Board was necessary. After discussion, I drafted changes to the Bylaws that set the terms of Trustees, Members, and Officers at three years except for one year for the Corporate Secretary, who now handled admissions, and the assistant officers. More delicately, the Trustees and Members were divided into three groups with staggered terms, the first to end the following year. These changes were adopted by the extant members. In addition, Hans Bethe, Mike Cohen, Dan Fivel, and George Stranahan became Honorary Trustees. (The turnover of long–time Trustees was not completed until 1980, when Durand, Gell–Mann, Kaus, and Pines all became Honorary together, another rather delicate negotiation since we had terms ending at different times. [Note 16])

The plans for the new building were complete, fund raising was nearly complete, and we assumed that we would retain use of Hilbert. Unfortunately, the AIHS–DU negotiations were still under way (they fell through later), and the Institute was only going to submit its master plan to the City later. We decided to apply for a building permit nonetheless. The final major funds were assured when David and I visited the Kresge Foundation in Troy, MI, explained our program and plans in person, and received a commitment for $50,000, to be committed that fall. The building permit was delayed for a year, and we had to get special extensions of their grants from the Fleischman and Kresge Foundations, not automatic since they had other, immediate demands on their funds. The Trustees all signed for the final construction loan of $45,000 in 21 equal shares, and the construction started in time for Bethe Hall to be available during the summer of 1978. The final cost was $158,360. A continuing–use agreement for Hilbert Hall was reached with the AIHS in August, and our facilities then remained the same until the reorganization of the campus and construction of the Smart Hall complex in the 1990s.

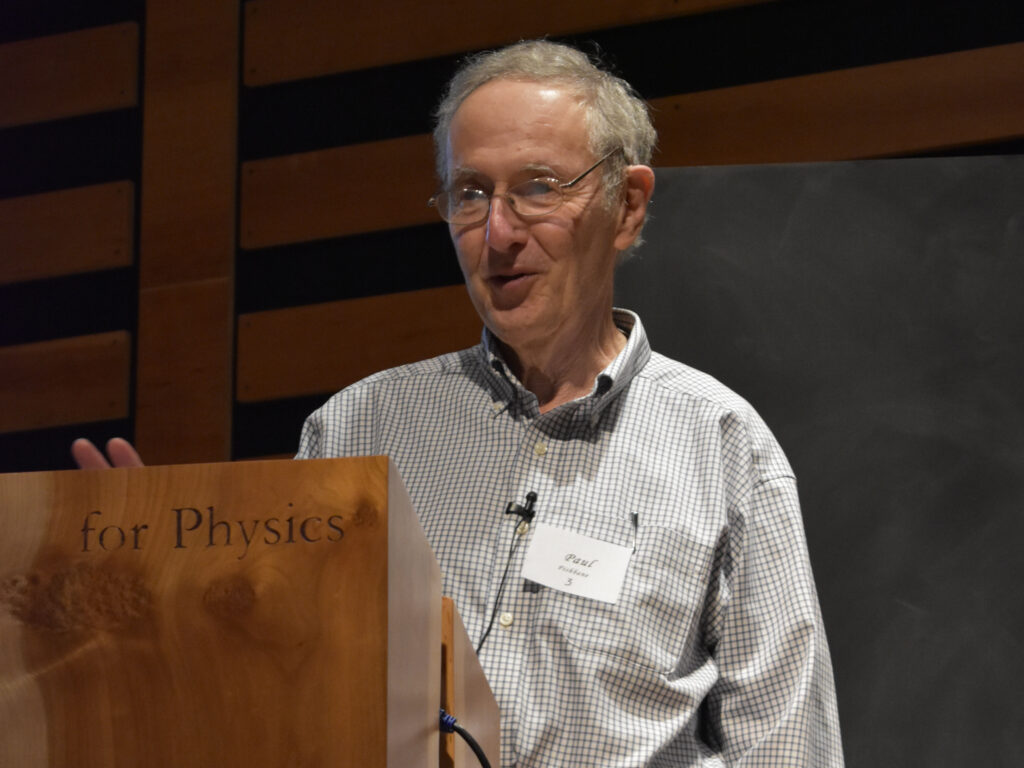

Paul Fishbane was elected President in July. He had first come to the Center in 1968 as my postdoc, and had become a Trustee in 1974. I was quite happy to have a young physicist as a successor, in line with my continuing belief that the Center should be turned over regularly to younger generations to run as they find best for their era, with the advice, if desired, of their predecessors. And I was quite happy to escape from the immediate demands of the presidency.

Notes

Note 1 The notes here, and the accounts of funding below, have been checked in the Center’s archives; they give only a sketch of the development of the Center. Records on early support and finances were traced mainly through correspondence, and later, through informal internal reports. The actual financial transactions and records through mid 1968 were handled by the Aspen Institute.

Note 2 Most of us handled the admissions/housing process at least once. It was all conducted by mail and telephone, plus a short meeting of a few people in later years

Note 3 LD records at Center.

Note 4 Correspondence between myself and George Stranahan, fall, 1967.

Note 5 An anecdote with respect to the visit told by David Pines was that he and Suzy Pines took Arnie sightseeing to Maroon Lake. Along the way, Arnie made a remark along the lines, “It is so beautiful here. Does anyone ever go to seminars and work on their research?” Margaret Gell–Mann, along for the ride, replied “Not usually!” It ultimately did not affect our funding.

Note 6 This history can all be traced through the reports of the Trustees meetings and the Executive Committee,plus some correspondence in the archives, especially from George.

Note 7 This was a widely representative and remarkable group: Robert O. Anderson (chair of Atlantic–Richfield and the AIHS), Julius Ashkin, Michel Baranger, Hans Bethe, Michael Cohen, Loyal Durand, Richard Ferrell, Daniel Fivel, Murray Gell–Mann, Marvin Goldberger, Peter Kaus, David Pines, Henry Primakoff, Frederick Seitz, George Stranahan, and Lincoln Wolfenstein.

Note 8 We were regarded somewhat as smart but brash youngsters, to be tolerated but perhaps not taken too seriously. Our participation in the Institute’s Executive Seminars led to some remarkable incidents, such as when R. O. Anderson tried to lecture Tony Leggett, an Oxford First in classics and later a Nobelist and Sir Anthony, on Greek history/philosophy; or when Stan Ulam, not identified to the seminar participants, quietly commented from the audience in response to a seminar discussion on the development of the hydrogen bomb.

R. O. (known to the physicists in the early days as “108 Anderson” for his reputed assets at the time) was a highly successful oil wildcatter and refiner who merged his company with Atlantic Refining and then with Richfield Oil to form ARCO. He was the chair of the ARCO board and more pertinently to us, the AIHS board, and was a Trustee of the Center for 1968-81. R. O. would sit patiently (and with bemusement) through our Trustees’ meetings, tell us about things such as his use of trickle irrigation on his Australian properties (he was interested in the environment; he also owned ~106 acres of ranch land in New Mexico) and Institute plans. He was generally sympathetic to the Center, invited us to many Institute social events, but never got the Institute to the point of giving the Center title to our buildings and land as that might interfere with the Institute-City negotiations on the zoning of the AIHS property overall. I lived two summers in the Frischman house, just behind his house on Francis Street, and often saw him in old clothes and his battered Stetson hat loading his kids in his old jeep in the afternoon to take them fishing, a typical Aspen summer activity and nice to see in such a high-level operator.

Note 9 The “lease,” rumored for many years to exist but, to our consternation, never found, was actually a formal letter of understanding between the AIHS and the newly incorporated Center in August, 1968. I located it a few years ago in a pile of correspondence in the archives. It covered the Stranahan and Hilbert buildings, and spelled out the Institute’s ownership and the Center’s privileges.

Note 10 I remember being mistaken several times for the (nonexistent) janitor by new participants when working around the buildings.

Note 11 There are undoubtedly some townhouses/condos included in this count –- I have not checked — but we still rented mainly houses for families. These were quite varied, ranging from small Victorians and primitive pan-abodes to larger houses used for bachelors. I lived for a few weeks in ~1965 in one of the latter, the Fairless house downtown, owned by the chair of U.S. Steel, and with a Dwight Eisenhower painting for decoration in the living room, a personal gift from Ike. The dinner conversations there were non-standard and quite stimulating, ranging over a variety of fields of physics and into mathematics — two other occupants were Ken Wilson and Brian Josephson.

Note 12 It was not unusual for the physicists on a hike to get into physics or other professional conversations. I remember a discussion with J. D. (BJ) Bjorken on the top of Pyramid Peak about symmetries, and the interpretation of gravity as a gauge theory, after we had completed a rather difficult route on the east ridge. On a different hike, Murray Gell–Mann got into a several–mile long conversation with our friend Cyrena Pondrom, a professor of English at Wisconsin and eminent expert on 20th century writers, on the interpretation of James Joyce (the originator of the term “quark”). She later commented with admiration that, no matter how far Murray got out on a limb, he never cut himself off (“He knew Finnegan’s Wake forwards and backwards!”).

Note 13 I would meet each summer with the astrophysics steering group to work out the timing of their three–week workshop, and participate in the discussion of possible topics to make sure the topic selected was appropriate for the Center’s program. The steering group handled the writing of the grant and decided how the funds were to be used.

Note 14 The library shelving was assembled by the physicists in residence. We have fond memories of Murray Gell–Mann and Heinz Pagels assembling a shelf rack incorrectly, so that the shelves would not fit; it was redone after they left the Center for the day.

Note 15 None of the active Trustees wanted to be the only one rotated off the Board in a given year, and with no fixed terms – and also no distinction between Trustees and Members – it was difficult to bring in new people in the numbers we needed.

Note 16 The change to the present governance structure, with Trustees and Members distinguished, with different numbers and clearly defined roles, did not take place until 1990, when I completely redid the Bylaws with the help of Mike Simmons and an ad hoc committee, and our lawyer Nick McGrath, an expert on non–profits.