In the fall of 1953 when I returned to my home in Aspen from an expedition to K2 in Pakistan, Walter Paepcke (despite doubts of my sanity for venturing to the Himalayas) hired me as Executive Director and Assistant to the President of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. To acquaint me with what I was to do he said, “The business leaders of the U.S. need to be exposed to the best and most creative minds in our country. They must be made aware of the founding ideas of American society. That means going all the way back to the Greeks, to the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the impact of modern science.” Paepcke said, “If someone doesn’t attempt to do this, America will suffer from a loss of the kind of leadership exemplified by the great societies of history.”

I asked, “Why businessmen?” and Paepcke responded, “If I may borrow a phrase from Willie Sutton: ‘that’s where the money is.’ American business is the driving force of our culture and if businessmen don’t understand where and what we have come from, we will have failed the founders. That means exposing them to the best philosophers, scientists, leaders of government, judges, theologians, and yes, even labor leaders. In the long run, I believe it will make their companies and their products better. That’s the essence of the Executive Program.”

Paepcke, a longtime trustee of the University of Chicago, had gotten to know Enrico Fermi and persuaded him to take part in one of the early sessions in 1953. Hans Bethe and his wife Rose visited Aspen and became intrigued with its engaging ambiance. Justice Hugo Black took part as did Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers Union and Reinhold Niebuhr. My charge was to work with the board of trustees and whatever connections I had or could forge to assure the flow of talent to the programs, not to mention recruit executive participants from the corporations. With all of that I became what I have described to friends as a kind of ‘intellectual madame.’

A teammate of mine on K2 was George Bell, a theoretician (who had done his PhD under Bethe) who had recently joined T-Division at Los Alamos, and George over the next several years was very helpful in finding a wide variety of talents from the various divisions at LANL. These included George Cowan, Carson Mark, Donald Hughes, Roderick Spence, James Tuck, George Gamow, and Norris Bradbury. We did not confine our interest in scientists to physicists, but also brought to the seminars Theodosius Dobzhansky, Herbert J. Muller, and Harlow Shapley.

I mention all of the foregoing as, in an important way, it was a kind of prelude to the physics enterprise. I believe the Aspen Institute was the first in the country to engage scientists in ongoing meaningful dialogue about the importance of science in a democratic society. This led to a National Science Foundation grant for “The Public Understanding of the Role of Science in Society” in 1962. The cumulative experience of scientists in Aspen led me to wonder whether some kind of alpine version for young scientists of the Institute in Princeton might be possible.

I met George Stranahan at a party at the Caudill’s in 1959 and we discovered a mutual love of science, the mountains, skiing, and fly fishing. I told him of the Institute’s interest in having scientists involved in its programs. He noted that he had wondered why scientists could not usefully exchange ideas in their various fields in the seclusion of the mountains. He was thinking primarily of theoretical physics which required no labs or machines and I mentioned my thoughts about multidisciplinary exchange.

This latter idea was fairly quickly discarded as it was revealed that in the atmosphere of the Cold War there was not significant federal funding for theoretical exchange in an interdisciplinary context. We also learned from our friends at Los Alamos that a significant population of physicists liked being in the mountains and that indeed there were some who even liked climbing them.

Focusing on physics, George made it clear that to assist the startup there would be funding available to build a structure providing offices and library space for the scientists. The support would come from the Needmor Fund (the whimsically named Stranahan family foundation). The support would be available if the Institute would be willing to incorporate what was beginning to feel like an amorphous gathering of free-thinking physicists.

At the time, summer of 1960, Walter Paepcke had sadly passed away, he providently had brought Robert O. Anderson, a University of Chicago graduate and very successful oil industry wildcatter into the leadership role of the Institute. Anderson, a great chance taker and proud of Chicago’s role in science, was “intrigued with a bunch of physicists bringing their salaries and spending their summers in Aspen thinking about God knows what.” This was in spite of one trustee who thought all scientists were “lefties.” So, after informing the Institute board, he gave us the green light.

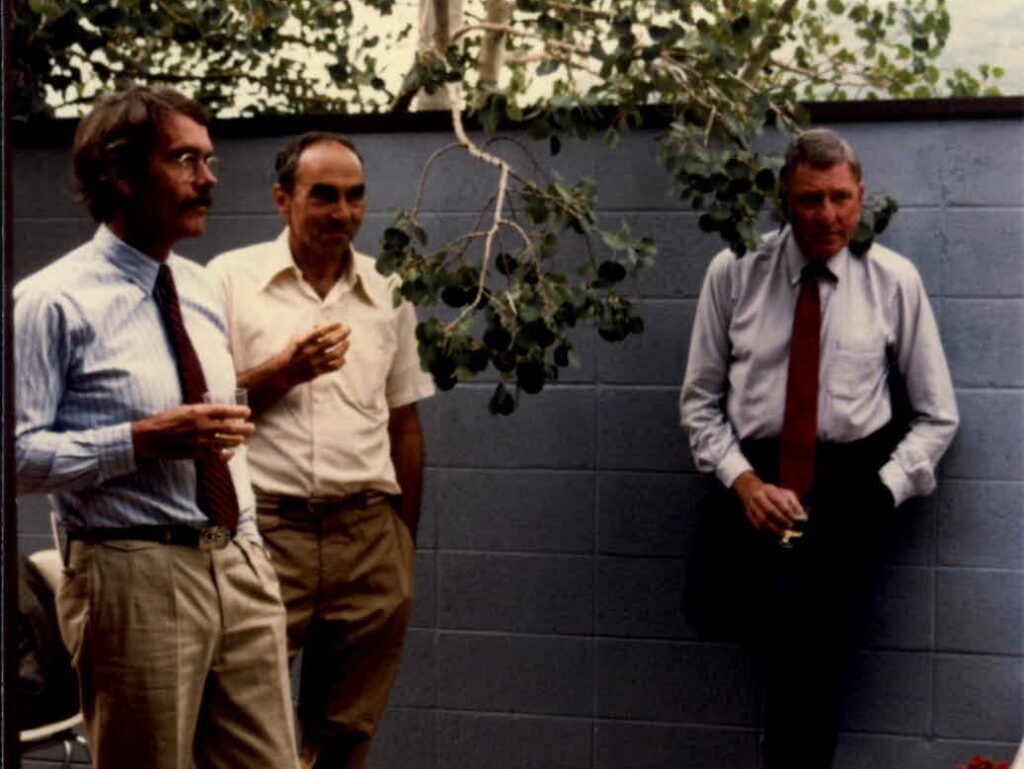

The “green light” from Anderson stipulated no funding from the Institute which, despite Paepcke and R.O. Anderson’s generosity, was at that stage of its career struggling for support. George and I therefore began a search for sources of money that would provide the basic support structure of the physics enterprise. We also needed to know who would and who should come, and to that end we turned to Michael Cohen, a professor at Penn and also a consultant at Los Alamos; Michel Baranger, a professor at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon) with whom Stranahan had worked towards his doctorate; and Lincoln Wolfenstein, also a professor at Carnegie.

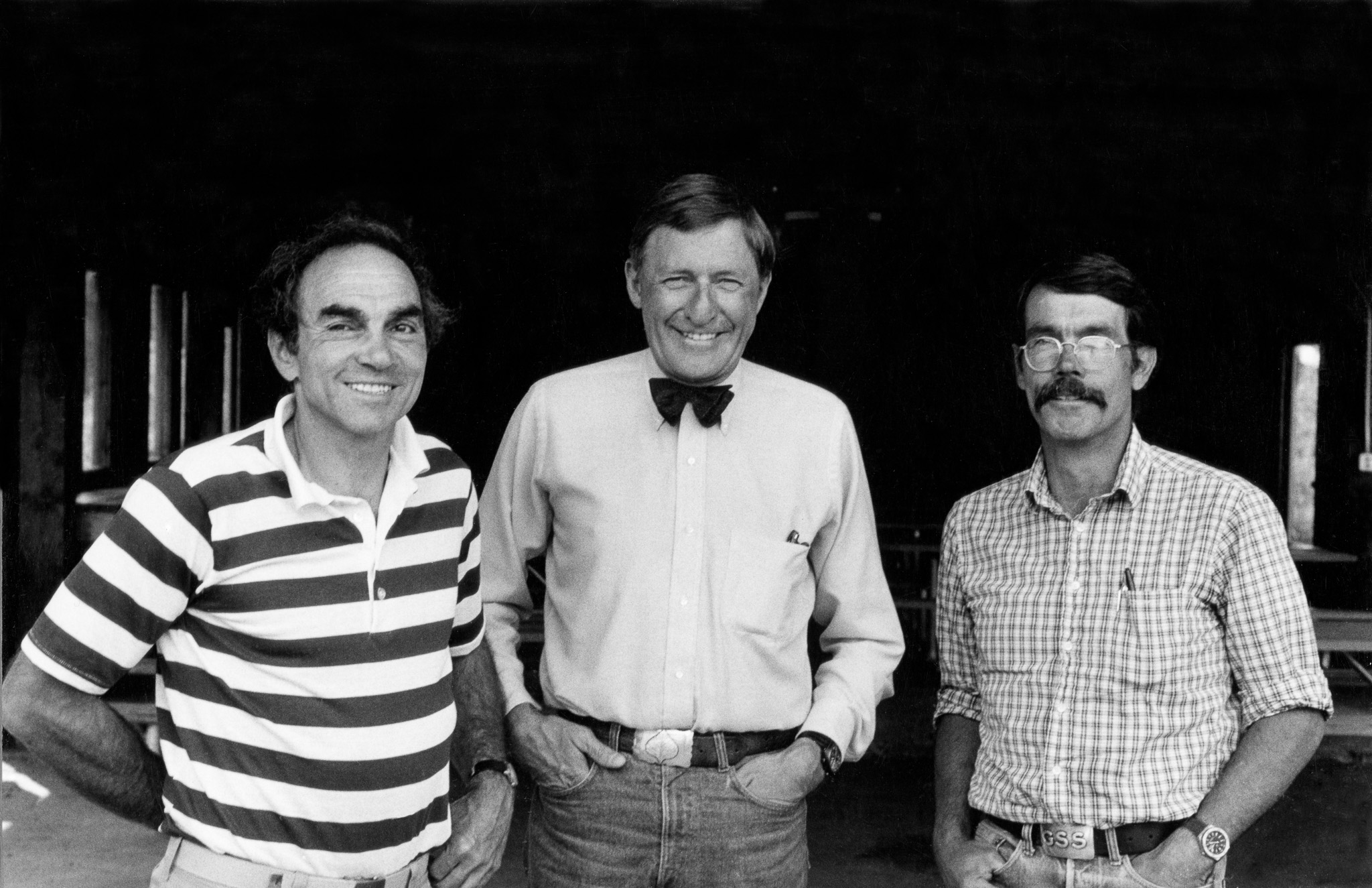

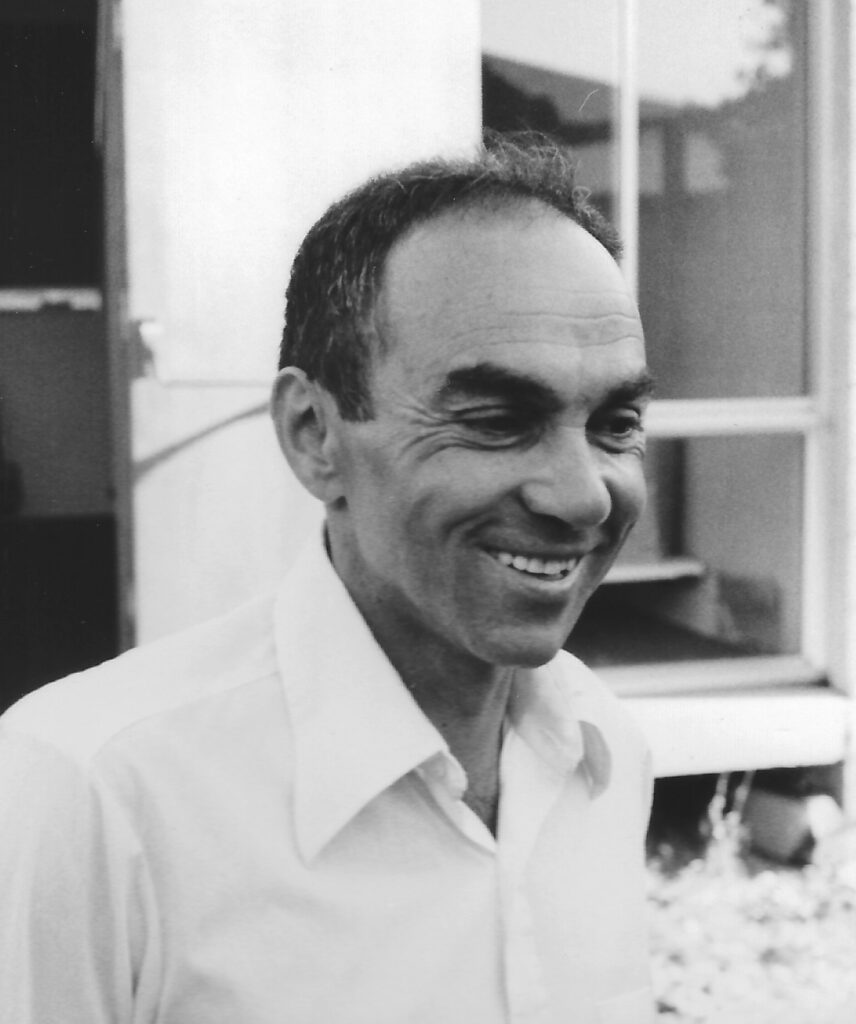

All three gentlemen contributed significant recommendations and Cohen expressed such enthusiasm and vision that he quickly became a partner in the founding. Cohen was not only very smart (in a non-physics sense, but I was also told he had done his PhD under Feynman), he was funny in a Groucho-esque kind of way and seemed to have a practical streak. Importantly, George, Mike, and I had become friends.

It was decided in the spring of 1961 that George, having secured the funding, would oversee the construction of the physics building, although he was unable to assign design of the structure to his architect friend, Sam Caudill, because of Bauhaus architect and artist Herbert Bayer’s relationship with the Institute. Cohen accepted the task of canvassing the physics community for participation of people who would bring their salaries and grants to Aspen. The list grew quickly and, we were assured, included some of the brightest people in the field.

My task was to seek operational funding in Washington or wherever it was available. Thanks to the Institute’s connection to IBM for the Executive Program, we were able to approach Dr. Emanuel Piore, IBM’s chief scientist, for a $25,000 grant (a pretty huge sum in those days). Next we made a proposal to Dr. Eugene Fubini, Director of Research at DOD, and largely because Bob McNamara had been a trustee of the Institute, we received a grant of $15,000. Fubini very kindly suggested we talk to Dr. Shirleigh Silverman at the Office of Naval Research which we did and to our surprise received a pledge of $20,000.

So we, in the late summer and fall of 1961, were underway on what has become (not without its trials) the Aspen Center for Physics. In my humble opinion, the Physics Center in Aspen has (despite its reticence for publicity and hornblowing) been one of the premier intellectual achievements of the past 50 years in America.