Introduction

I made my first visit to the Aspen Center for Physics in June of 1969. The Center had been in operation since the summer of 1962 and from the beginning one of its founders, Michael Cohen, had been urging me to apply for a visit. There was a selection committee. I had known Cohen, one of the few PhD students of Richard Feynman, ever since we overlapped at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton during the academic year of 1957-58. Cohen was now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He was also very persuasive, but I had been spending my summers doing physics in Europe. Now I was going to try Colorado.

I flew to Denver and rented a Volkswagen at a place called Rent-a-Bug. I was assured that it was just the ticket for mountain driving. got directions for getting to Aspen and was instructed to go by way of Independence Pass which would save a good deal of time. took what s now Interstate I-70 until the turn-off to Leadville. Many of these Colorado mountain towns have mineral names such as Gypsum or Silt. Once on the turn-off it was clear that I was in the high mountain country and indeed I passed the highest mountain in Colorado, Elbert. Then I turned off onto the road to Aspen. The road went steadily upward to the pass at over 12,000 feet. It marks the Continental Divide. Water to the east flows east and water on the Western Slope flows west. I stopped to take in the view – a sea of snow covered mountains and then headed down the winding road to Aspen, a descent of about four thousand feet.

I had a map as to how to find the Physics Center. The highway down which had come-82-turns into Main Street and then all you had to do was go to Sixth Street and turn north. At the end of Sixth Street was the Center. There were two buildings on the campus. The more formal concrete structure was called Stranahan Hall. I had no idea who Stranahan was or why he should have hall named after him.

“I had no idea who Stranahan was or why he should have a hall named after him.”

The other building-a sort of wooden barrack-was called Hilbert. I knew who Hilbert was. He was one of the greatest mathematicians of the twentieth century. Some of his mathematics is used in the formulation of the quantum theory. He once remarked that theoretical physics was too hard for physicists. He also once said that if the ten smartest people in the world got together they could not invent anything as stupid as astrology. There was every reason to name a building for him. I learned much later that the building had been used in a study of a high-energy accelerator, now Fermilab, and that the director of that study, Robert Wilson, had arranged to donate the building to the Center.

My instructions were to report to Stranahan to learn where would be living and acquire a key for a same and directions as to how to get there. The instructions told me that would have a one-bedroom condominium in a complex called Glory Hole-a reference to Aspen’s mining days. It was on the east side of town. I parked my “Bug” and noticed a couple of horses grazing on the front lawn. The condominium was simple and pleasant. I unpacked and went by foot to look for some place to have dinner. The restaurant I came across was called the Wienerstube and, since I had spent some time doing physics in Vienna, thought that a schnitzel would be just the ticket. After dinner ventured further into town. I soon came to the Wheeler Opera House, which also dated from the mining days. There was the sound of music and laughter coming from below. Upon inspection it turned out to be a bar called The Pub. Down I went. The bar itself was a very wide affair with a metal top. I sat down. To my left was a very attractive blond girl dressed in what I would call Western Casual. I was beginning a conversation with her when down the very wide metal bar there was a fellow being slid along at rather high speed. My neighbor noting my astonished expression said, “You must be from the East.” That was my introduction to Aspen.

I have now been coming for some forty years and since 1995 have been a part-time resident. I have seen the town grow and change and the Physics Center grow and change along with it. I want to give some of this history and that is what these chapters are about.

Chapter I: A Spark Plug

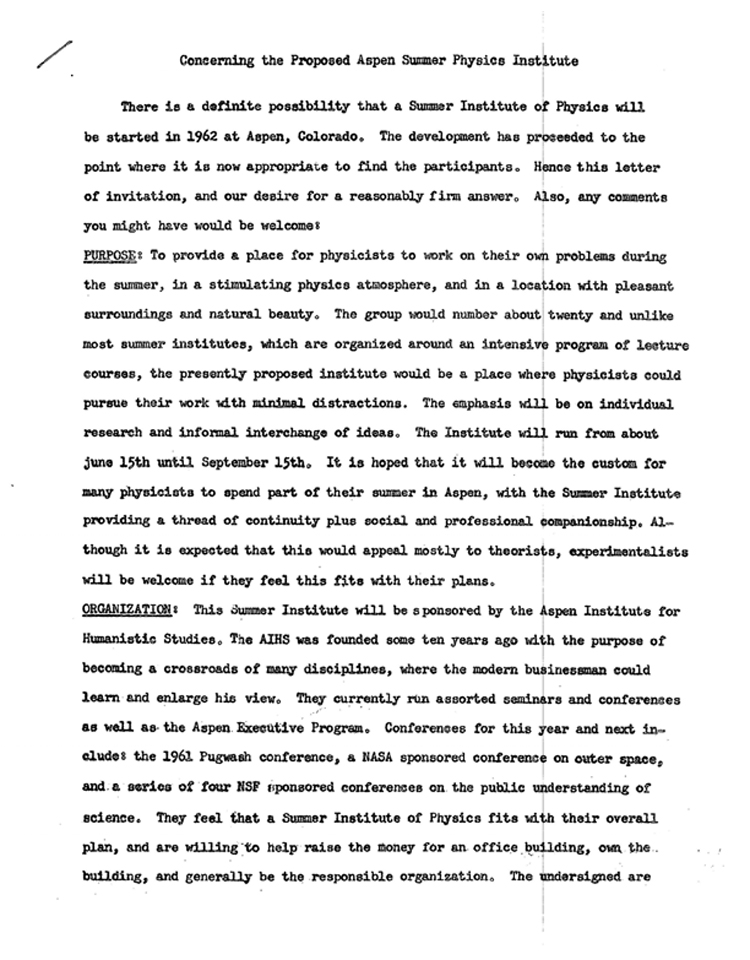

George Stranahan

George Stranahan, portrait by Bernice Durand

The Stranahan family came to the United States from Ireland in the nineteenth century. By the turn of the century Frank D. Stranahan was working as a night clerk in the Tremont Hotel in Boston. He earned enough money to put his younger brothers through Harvard. His brother Robert was the first Stranahan up to then to have graduated from Harvard. Robert married right after graduation and soon had “a daughter on his knee,” George Stranahan said in an interview for this book.

The two brothers opened a bicycle sales and repair shop in Boston apparently financed by their mother. The Stranahans thought that the automobile was the next big thing and they decided that their best bet in growing their business was through spark plugs, which in an internal combustion engine ignite the combustible fuel mixture at each cycle. The brothers had financed a French bicycle and motorcycle racer named Albert Champion who came to the United States largely to avoid being drafted into the French army. One of the curiosities of bicycle racing in France at the time was that the racers would race in a velodrome while being paced by small motorcycles. Champion couldn’t find parts for his motorcycles in the U.S. so he started making spark plugs and selling them to friends. The Stranahans invested in and eventually acquired his fledgling business, Champion Ignition Company. They then made some of their own innovations, such as using porcelain as an insulator, a very important improvement for spark plugs. Up to that time they had to be changed every hundred miles or so, but the new insulator lasted a thousand miles. One curious consequence of their porcelain activities was that during the Second World War they made the porcelain filters that were used in one of the processes to separate the uranium isotopes used for nuclear weapons at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The brothers first moved to Rochester, New York and then to Toledo, Ohio, which was then the center of the automobile industry. They approached Henry Ford and convinced him that their new porcelain insulated spark plugs were just what he needed for his automobiles. In fact they offered them to Ford at cost. The brothers realized that since the spark plugs would have to be changed every thousand miles, the consumer would regularly be paying full price. It was a brilliant business model. It was such a good idea that before parting ways with Albert Champion, the Stranahans had sent him to Detroit to sell the idea to Alfred Sloan at General Motors. Communication was by telegraph in those days and the Stranahan brothers sent several to Champion to ask how things were going. They kept getting messages from Champion that he needed more time. Indeed he used the time to make his own deal with Sloan. Now there were two spark plug manufacturers – Champion – owned by the brothers and A.C. owned by Champion and General Motors.

Frank had an only son named Duane who also went to Harvard and majored in English literature. It was inevitable for Duane to go into the family business. But Duane’s interest was aviation. He got his pilot’s license in 1930 and took charge of Champion’s aircraft engine spark plug business, but only after he had done apprenticeships starting in the mines in Colorado where the material for the ceramics was found. He married Virginia Secor and they had six children, four boys and two girls. The second oldest boy, George, was born in

Toledo in 1931. The family lived in a fashionable suburb, Perrysburg, where George grew up with a cook, a nurse and a gardener who called him “master George.” By age twelve George had decided that he was going to be a scientist. He had been sent to a progressive private school, one which his mother had attended. But it was not close to his home and George found it very difficult to make friends with people his own age who lived in his neighborhood. “When I came home from school I would go to my room where I had books on astronomy and books on the Himalayas. That’s how I would spend my time.” [Parenthetically on one of my trips to the Mount Everest region in Nepal, I found Stranahan and his wife comfortably ensconced in a tent. They had been trekking for weeks.] At this time it was customary for the children of what Stranahan refers to as the “nouveau riche” of Toledo to send their children to eastern boarding schools so that they could get into a good college. Stranahan was sent to Hotchkiss in Lakeville, Connecticut. Hotchkiss offered a classical education with Latin and Greek and ancient history. There was little science and Stranahan came to despise the place. He was, as he said, “lonely and nerdy and not from the East coast. I had a difficult four years.”

When it came time to apply for college he thought of MIT but he decided that he had had enough of the East coast. That applied to Harvard and Yale as well so he chose Caltech in Pasadena. He did very well on the entrance examination and was accepted. This was 1949 and much of his class was made up of returning soldiers on the GI Bill, some of whom had been recently been flying B–17 missions over Berlin. Stranahan again felt out of place. He did not much like the course work and fell in with some older students who spent their time playing partnership “hearts.” There is a good deal of strategy involved. It was an excellent training for bridge at which Stranahan became quite expert. His older hearts partners explained to Stranahan how he could game his Saturday quantitative analysis chemistry course and spend the time on the beach. Stranahan did not like the beginning physics courses either and began reading things on the quantum theory and relativity on his own. As a result of this he graduated 124th in a class of 126. However Caltech had a program for seniors which allowed them to become an apprentice to some professor of choice. Stranahan picked Leverett Davis Junior who was an astrophysicist.

Davis was an interesting man. He had taken his PhD at Caltech in 1941 and then spent the war working on rockets. He joined the Caltech faculty in 1946 and taught there until his retirement in 1981. In the 1960’s he became involved with the space program. He was also a very nice man. Stranahan had made a wise choice. At the time Davis was interested in polarized starlight. This is light in which the waves oscillate in some fixed direction with respect to their direction of propagation. The starlight did not start out polarized but it interacted with some interstellar “dust” which must have also been polarized. The only way this could happen is if the dust had interacted with magnetic fields. Thus the polarized light was an indirect way of measuring interstellar magnetic fields. The first thing that Davis gave Stranahan to look at were pages and pages on yellow foolscap with algebraic calculations. They concerned the collision between a dust cloud and hydrogen gas. Stranahan recalled,” He said that I should check the algebra. I had never done such a thing–forty or fifty pages of algebra. It was wonderful. I felt as if I was doing something real. Then he said “I have an interesting problem you can do all by yourself.” The problem concerned the degree of polarization and hence the strength of the magnetic fields. Stranahan was able to publish the results in The Astrophysical Review a prestigious peer–reviewed journal. He was then in the odd position of having a mediocre academic record but also having a published research paper. He sought advice from Richard Feynman who had recently joined the faculty and had a large tolerance for the eccentric.

Feynman said to Stranahan, “You’re not going to get into a very good graduate school. Let me give you a list of competent ones.” On the list was the Carnegie Institute of Technology–now Carnegie–Mellon–in Pittsburgh. Stranahan thinks that Carnegie was glad to have him because he was a “Caltechy” and he had chosen them over Caltech. In truth it was unlikely that Stranahan would have gotten into the graduate school at Caltech. As it happened Carnegie had a very fine physics department whose leading light was Gian–Carlo Wick who had been there since 1951. Wick had been one of Enrico Fermi’s assistants in Rome and then accepted professorships in other Italian universities, finally returning to Rome during the war. After the war he went to Berkeley but when the Regents of the University of California introduced a loyalty oath that the professors had to sign, he quit, which is how he ended up at Carnegie. He ultimately became a professor at Columbia University. He had an international reputation as one the best physicists of his era.

By this time Stranahan had become sufficiently interested in physics that he decided to work hard at it. But there was a problem–the Korean War. Stranahan was of draft age. He noted that Perrysburg, where he lived, was a farm community and that they were not going to draft farm boys who were needed to grow crops, but he was a perfect candidate. His mother told him that he should promptly marry his child–hood sweetheart and perhaps as a married man he might be deferred. But then his mother gummed up the works. The postmaster in Perrysburg also was in charge of the draft board. The Stranahans had a subscription to Life magazine. The postmaster took the new issues home to read before he delivered them. After a year of this Mrs. Stranahan, who was a very forceful personality, told the postmaster in no uncertain terms that he should take someone else’s magazine home. He responded by saying that he was going to make sure that all her boys were drafted. Stranahan found himself at Fort Knox, Kentucky where he participated in morning bayonet exercises, which he found ironic considering that we had the atomic bomb. Stranahan was sent to Fort Monmouth to study radar repair. Considering his record at Caltech he was amused by the fact that he scored close to 100% on all the tests. By this time Stranahan had had his second child. Despite this he was scheduled to be shipped overseas. But bridge saved him. He had become the bridge partner of the battalion clerk. He was so good that whenever Stranahan’s name appeared on the list to be shipped out, the battalion clerk simply erased it. “My wasted life at Caltech saved me from going to Korea.”

Physics in Aspen Colorado?

While he was in the army Stranahan’s wage was $50 a month with an additional family allowance of $150 a month. Out of this he was paying a monthly rent of $80. At this time his parents came to visit him. They explained that his paternal grandmother had died leaving his father as her primary beneficiary. There was a tremendous tax burden which could be lifted if some of the money was given to her grandchildren. This is what they were going to do. Stranahan inquired whether he could draw an additional $200 a month from it. Since his share of the legacy was $3 million, this was not a problem. Stranahan got out of the army in 1956 and returned to Carnegie to do his PhD. One of Wick’s students, Richard Cutkosky, was then a young faculty member and he took Stranahan on as his student. But before Stranahan returned to Pittsburgh for the fall semester he decided that he needed a couple of weeks to himself. He returned to Aspen, Colorado where his family had come to ski as early as 1949. Aspen in the summer was really nice so he decided that the next summer he would come back with his family. They rented a five–bedroom house for $400 for the summer. The owner tossed in the use of his jeep. He repeated his summer Aspen visits for the next two summers. At first he thought that he could do his thesis work just as well there as in Pittsburgh. All he needed was paper and pencil and a few books. But he found that he couldn’t work. There were too many temptations such as fishing and hiking. Also something was missing, other physicists to talk to.

Physics is a very social activity although to an onlooker it may not seem so. The example of Einstein is cited. Einstein once said that the ideal occupation for a theoretical physicist was as a lighthouse keeper. There would be no students to teach and one would be free to do one’s work without interference. But Einstein overlooked the context. He had had a fine education in the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich where he had learned basic physics and mathematics. It is true that after he became a patent inspector in Berne in 1904 he did not have many people to talk to about physics. But soon after his great papers of 1905, including the work on Special Theory of Relativity, he was in contact with many other physicists. Einstein’s scientific correspondence is so voluminous that one wonders where he found the time to do anything else–a lighthouse keeper indeed. I am persuaded that scientific genius is universally distributed. There is about as much chance of finding such a genius in Nepal as in Denmark. The difference is context. In Denmark a scientific genius like Niels Bohr is recognized and nurtured while, at least until relatively recently, a scientific genius in Nepal was probably unnoticed or became a religious figure. At some point in the summer of 1959 Stranahan found that he could no longer work. His mind simply shut down. “Physics simply does not work as a solitary activity. You have to have somebody to talk to. We need a physics think tank in Aspen.” At this point Stranahan was introduced to Robert Craig.

Robert Craig and the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies

Craig was and is an interesting character. In 1949 he took degrees in philosophy and biology from the University of Washington in Seattle. He had served in the navy during World War II and had participated in some major amphibious operations. During the Korean War he taught mountain and cold weather techniques at Fort Carson in Colorado. That he taught mountaineering to soldiers was not an accident; Craig was one of the best American climbers. He had been selected for an American expedition to climb K2. K2, on the Chinese–Pakistan border, is the second highest mountain in the world and technically more difficult than Everest. High on the mountain one of the climbers, Art Gilkey, got thrombophlebitis, a blood clot condition which can be fatal even if treated at sea level. The rest of the climbers decided that they had to get him down as soon as possible and began a very difficult descent with an injured man. At one point they had a fall and were held on a belay by Pete Schoening. Gilkey had been tied off before the fall and when they went to look for him he had disappeared. What happened no one knows. From 1953 to 1965 Craig held various executive positions at what was then known as The Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. This had been the conception of Walter Paepcke, chairman of the Container Corporation of America which had its headquarters in Chicago. Paepcke and his wife Elizabeth had been coming to Aspen since the mid 1940’s when there was hardly a town. Paepcke saw its potential as a ski resort and began investing in it. He also saw its possibilities as a cultural center where business people like him could enjoy the out of doors and enlarge their cultural perspectives. He was a trustee at the University of Chicago and was impressed by the educational experiments of its young president Robert Hutchins. Hutchins and the philosopher Mortimer Adler conceived the idea of studying what they identified as the “great books.” Adler was particularly fond of Aristotle and the businessmen who came to Aspen starting in 1950 got a good dose of the Stagirian. Of science there was none.

A mutual friend arranged for a dinner where Craig and Stranahan met. He explained to Craig his idea of having a research center in physics in Aspen. “Bob immediately liked the idea,” Stranahan recalled. Stranahan had a clear idea of what this center was not going to be–a summer school. At the time there were summer schools in physics. Two of the best known were in the French Alps at Les Houches and at Cargèse on the island of Corsica, where I taught for three summers. A friend of mine referred to these activities as the leisure of the theory class. These places offered mini–courses in advanced subjects to graduate students. The faculty, distinguished senior physicists, got a free semi–vacation in return for teaching and writing up their lectures in a publishable form. Stranahan wanted none of this. There were going to be no students and no courses. On the contrary, physicists could do their research free of any academic responsibilities. It was recognized that these would be largely theoretical physicists since experimenters would need equipment and staffs to help run it. Craig agreed. Stranahan recalled Craig’s saying, “We have an Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. People come from industry and academia. They cross in Aspen and then they all go home. We need something active where you can see people thinking, something permanent.” By this time Walter Paepcke, who was to die in 1960, was no longer active and the new regime at the Institute, which was going to be headed by the oilman R.O. Anderson, was not yet in place so that Craig was in a position to make all the decisions with the consent of the existing board of directors who approved having a physics division of the Aspen Institute under the condition that the Institute would not be expected to provide any of the money.

This was now 1961. Stranahan had just received his PhD and he set about raising money for the new physics institute. He made a deal with Craig. Stranahan would raise all the money he could from Aspen locals and from the industrialists coming to the Institute and he would personally cover whatever shortfall there was. There was going to be a building. The building cost $85,000 and Stranahan put in $38,000. But well before there was a building, Stranahan had begun consulting physicists as to how to operate such an institution. One of the people he consulted was one of his teachers at Carnegie, Michel Baranger. Baranger said, “You must get to know Michael Cohen. Cohen who consults at Los Alamos has this dream of making a tent city outside Los Alamos where physicists could just come with their summer salaries and just do their physics. You need to meet Cohen.” The irony is that at the time that Stranahan was at Caltech, Cohen was there doing his PhD thesis with Feynman. They had never met and now Cohen was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. When he heard about it, Cohen was immediately interested. He, Craig and Stranahan met in the airport in Pittsburgh. Stranahan reported that Cohen said, “I know everybody in physics and Craig said that he knew people in Washington. My job was to make sure we had a building. Craig’s job was to make sure we had a government grant and Cohen’s job was to make sure people came, and sure enough it worked.” In the summer of 1962 the Stranahan building at the end of the then unpaved Sixth Street on the west side of Aspen opened its doors to the first group of physicists to visit what became the Aspen Center for Physics.

Chapter II: A Start

Stranahan got his PhD in the fall of 1961. He had an appointment as a research associate at Purdue University. It had become clear that Aspen was going to be a permanent part of his life so he used some of his inheritance to lay down roots. He bought sixty acres of land in nearby Woody Creek for $35,000 and he built a very large log home with a magnificent view of the mountains for $25,000. He had raised or supplied enough money for a physics building. It was time to begin building it. Stranahan had become friendly with a local architect and had assumed that he would have his choice of architects. But the Aspen Institute owned the land on which the Physics Center was going to be located. Indeed the Center was the Physics Division of the Aspen Institute, which meant that they did all the bookkeeping and had the non–profit status. It also meant that they owned whatever building would be constructed even if Stranahan’s money had helped to make it possible. Hence it was they who would choose the architect and not Stranahan. They insisted on choosing Herbert Bayer who had designed the buildings on the rest of the campus. Bayer, who had a very important influence on the architectural look of Aspen, had an interesting curriculum vitae.

Herbert Bayer, Architect

Bayer was born in Austria in 1900. After studying and working with various artists in Germany and Austria he joined Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus where he studied with people like Wassily Kandinsky. He then became the director of printing and advertising at the Bauhaus. In 1928 he became the art director of the German Vogue. He remained in Germany even after people like Gropius had left, and he even designed a brochure for the 1936 Berlin Olympic games. But in 1937 his work was designated as “degenerate art” and the next year he left for New York. In 1946 Walter Paepcke hired him to come to Aspen and plan the renewal of the town. One thing that he did was to participate in the renovation of the Wheeler Opera House. This was a magnificent structure that had been built in 1889 at the height of the silver boom. Like much in the town it had fallen into disrepair during the “Quiet Years” after the price of silver had collapsed and before Walter Paepcke decided to rejuvenate the town.

Now Bayer was to design the building for the Physics Center. Bayer brought back a Bauhaus design to be made out of handmade stone–block structures with a bid of $225,000–vastly more than any money that had or could be raised. The Institute instructed Bayer to build it out of cement blocks. It was not going to be ready until the middle of the summer. In the meanwhile Craig supplied office space at the Institute. Stranahan had given the design of the building a good deal of thought. He had decided that the physicists should be paired up two to an office. There would be no students. A good collaborative arrangement among theoretical physicists is usually in twos. There would be ten offices or a total of twenty physicists. There would be a small common room which would house the library, Stranahan bought all the books and the subscriptions to a few journals like the Physical Review. There were, Stranahan decided, not going to be any seminars. People would stay in their offices and work. As the summer evolved the physicists decided that they needed seminars so chairs were set up in the common room.

The First Year: 1962

At the entrance there was a desk for a receptionist. The choice that summer, Elizabeth Baldwin, was hired by Craig. Since she had worked in a bank she was known as “Betsy Bank.” Stranahan recalled that she was “young and cheerful and tolerant.” In dealing with physicists the latter was important. The business model, if you can call it that, was very different from the rest of the Institute. The Institute catered to wealthy businessmen who could afford to spend a high tuition to enhance their cultural dimension. They would live on the Institute campus where there was also a restaurant. It was 1.4 miles from the center of town near a river. From time to time they might frequent one of the local restaurants such as the Copper Kettle or the Golden Horn which had national reputations. There was a shuttle to take Institute people into town. The physicists on the other hand, Stranahan excepted, were living on modest academic salaries. They needed accommodations in town rented from the locals. One of Betsy Bank’s jobs was to find reasonably priced rentals. Here she could collaborate with the Aspen Music Festival and School which Walter Paepcke also helped to found in 1949. The musicians and their students also needed rentals in town so Betsy Bank was able to collaborate.

The physicists would not receive any money from the Center. What made the visit possible financially for most of them was what was known as the “summer salary,” While one received checks from one’s university every month, the appointments were usually for the academic year which did not include June, July and August. If one had a government grant from say the National Science Foundation, some of this could be used to pay oneself for at least part of the summer months–if one used that time to do the research for which the grant was intended. Stranahan felt that the physicists who would be accepted to come to Aspen would have grants and summer salaries. There was, as one might imagine, no shuttle to town. Quite soon there were free bicycles the physicists could borrow for the commute. There was little reason to have a car unless one was going to hike or climb somewhere out of town. The physicists brown–bagged their lunches at the Center. The Center got a grant from the Office of Naval Research for $15,000 of which fifteen percent went to the Institute for overhead. It was used to pay things like Betsy Bank’s salary and the electricity and water.

That first summer there were forty–one physicists staggered in different time periods from June through August. (See the appendix to this chapter for the list.) The building became available in mid–summer. The list of physicists from that summer is quite interesting. They came from all over the country and from many different universities. There was even one from Varian Associates, a California company that was involved with electromagnetic equipment. A few listed their “specialization.” Most of these were in high energy or elementary particle physics. This was the hot subject of the day. The plethora of recently discovered particles was beginning to fit into fascinating mathematical patterns. To a theoretical physicist this was irresistible. There are two women on the list, both wives of attending physicists, although Fay Selove, Walter Selove’s wife, was a distinguished physicist in her own right. A remarkable letter of invitation had been sent out under the signatures of Baranger, Cohen, Stranahan and Lincoln Wolfenstein–Baranger and Wolfenstein were both from Carnegie Tech. The letter, reproduced in the appendix, describes the nascent organization. It even suggests that the larger accommodations should cost about $125 a month! It is cautious about making too much of a public announcement since the facilities were going to be limited and gives a short list of distinguished physicists who have already agreed to come.

It is an interesting list. There is a wide distribution of institutions but only one from industry, Arden Sher from Varian. There are no participants from European institutions although one recognizes people like Bethe and Kurt Symanzik who were originally from Germany. Symanzik was one of the most distinguished mathematical physicists of his generation. Indeed, the list is full of distinguished physicists. It is noticeable that there are almost no women and no racial minorities. This reflected the state of the field at that time. In the next years this would change dramatically. Most of the physicists on the list would have described themselves as elementary particle or high–energy physicists. There were a few condensed–matter specialists but no astrophysicists except for Bethe who was a polymath, and certainly no bio–physicists. That also changed. The Center would soon attract people from industrial laboratories like IBM and Bell Labs, and there would be many more from government laboratories like Los Alamos. The 1962 list is short. A current list includes over 1,000 physicists visiting annually in summer and winter.

Hans Bethe

One of the early visitors was Hans Bethe. He came officially for the first time in 1965. He was one of the most distinguished theoretical physicists of the twentieth century. He made very important contributions in every branch of physics and because of his Los Alamos experience had become a spokesman for the control of nuclear weapons. His presence at the Center lent a gravitas to the place. His effect on the Center was so significant that I am going the present a profile of his life.

Bethe was born on July 2,1906 in Strasbourg which was then part of Germany. For a biography, see my Hans Bethe, Prophet of Energy, Basic Books, New York, 1980, the pages of which are cited below. His father was a Protestant physiologist at the university. His mother, who was Jewish, also came from a medical family. Bethe showed mathematical skills at a very early age. By the time he was fourteen he had taught himself the calculus from a book his father had. By this time the family had moved to Frankfurt and in 1924 Bethe entered the university there. From the point of view of physics the curriculum was rather limited and one of his professors told Bethe that he had to go to Munich to study with Arnold Sommerfeld. Not only was Sommerfeld an outstanding theoretical physicist but he was one of the truly great physics teachers. The number of his students such as Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli who went on to win the Nobel Prize was legion. Bethe had a couple of letters of recommendation and Sommerfeld said to him, “All right, you are very young, but come to my seminar.” [Hans Bethe, p. 14]. Bethe described the scene, “Sommerfeld had a huge office lined with books, and next to it was an equally huge office for his official assistant. And then there was another room of just about the same size which was simultaneously the library and the abode of everybody else. All the foreign postdoctorals and the German graduate students–eight or ten of us–sat in that room. There was an enormously long table, and we sat at that table as best we could. Later on, when I went back after my doctor’s degree [Hans Bethe, p. 14] on a fellowship, I got a desk in a separate room. But what a room! Most of it was occupied by a spiral staircase leading to the basement. There was just enough space for a desk and for people to pass when they went up and down the staircase which they did all day long.” [Hans Bethe, p. 14]

Sommerfeld gave an advanced course and then there was the seminar. It was once a week for two–and–a–half hours. Bethe said that Sommerfeld would occasionally interrupt with what sounded like a stupid question. The question usually went to the heart of the matter and frequently revealed that the speaker had not understood the problem he was dealing with, in which case Sommerfeld would explain it to him. Because of his eminence, Sommerfeld got preprints of the important papers in theoretical physics and in 1926 he got Schrödinger’s papers on wave mechanics. This gave Bethe the opportunity to learn the theory from its inception. He wrote his thesis on X–ray interactions with crystals and got his degree in 1928 and then had to look for a job. Sommerfeld had left for a sabbatical trip around the world and could not help. Jobs were very scarce and many PhD’s went into high school teaching. Bethe recalled that the job situation in Germany [Hans Bethe, p. 14] was as bad in 1928 as when he came to the United States in 1935 in the midst of the Great Depression. But Bethe did get a small job at the University of Frankfurt and then he got an offer to be the research assistant of P.P. Ewald in Stuttgart, a noted crystallographer who had read Bethe’s thesis. Bethe told me, “I was considered a child of the family. They invited me very often for dinner. They invited me to go on walks with them on Sunday, and if they didn’t feel like going themselves they asked me to take the two older children–a boy fourteen and a girl twelve–for walks by myself, which was also very nice. The girl, Rose, later became my wife, so I really did become one of the family. The arrangement back in 1929 was a very happy one, and especially happy for me because my parents had been divorced two years before.” [Hans Bethe, p. 23] One of Bethe’s “duties” was to give a course on the new quantum mechanics to Ewald and all the young assistants in the physics department. This happy arrangement came to an end when Sommerfeld returned from his trip and demanded Bethe back. That is when he got his own room.

By 1928 Bethe found that things were beginning to go wrong in Germany. Many of the young people he talked to at the university were fixated [Hans Bethe, p. 23] on the injustice of the Treaty of Versailles which ended the First Word War and spoke about the renaissance of an imperial Germany. There were even a few physics students in the nascent Nazi movement. Bethe was happy to get to Rome on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship after a time in Cambridge University. The physics in Rome was dominated by Enrico Fermi who seemed to Bethe to be like the bright Italian sunshine. They wrote a paper together after two day’s research which Fermi typed himself. Bethe told me that Fermi taught him how to write a scientific paper simply and clearly. In 1931 Bethe returned to Germany which was in a state of deep depression with banks failing and the like. But Bethe did not then think that the Nazis would take over. One of the physicists who came to work with Sommerfeld at that time was Lloyd Smith from Cornell, a connection that in a few years became very important to Bethe. In early 1933 Hitler took over Germany and the first racial laws were promulgated. Bethe was on a ski trip to Austria and when he got back, one of his students told him that a list of people who had been fired from the university in Munich because they had some Jewish ancestry, had been published in the newspaper. This way did Bethe learn that he had lost his job. Sommerfeld immediately set out to find jobs for his Jewish students in Germany but to Bethe it became clear that he had to leave the country. Fortunately he was offered a job at the University of Manchester, but in 1934 he got a cable from Cornell offering him an acting assistant professorship which paid $3,000 a year. Bethe went and despite offers from almost all the leading universities, never left.

When the war broke out Bethe was not yet an American citizen so he could not get clearance to work on any of the classified military projects, so he made one up. He worked on the penetration of armor by projectiles. The paper he wrote became a classic in that field. It was classified which meant that Bethe could not read it until later after he became a citizen in 1941 and had his clearance to work on the atomic bomb. In the late 1930’s Bethe wrote two monumental review articles on everything that was then known about nuclear physics. They became known as “Bethe’s Bible.” In March of 1941 Bethe received a phone call from Robert Oppenheimer in which, in a coded way, Oppenheimer managed to convey the fact that he was organizing a small group at Berkeley to consider the possibilities of making nuclear weapons. On the way to Berkeley, Bethe stopped in Chicago and saw enough of Fermi’s work on the first nuclear reactor to become persuaded that nuclear weapons were a real possibility. Edward Teller was then in Chicago and the two of them went west by train. In a private compartment they discussed the possibility of making a hydrogen bomb, a discussion that continued throughout their stay in Berkeley and even on walks in Yosemite. In the spring of 1943 Los Alamos was created and Oppenheimer made Bethe the head of the theory division. One of its members was the young Feynman who had just gotten his PhD from Princeton. His arguments with Bethe became legendary. Bethe kept Feynman in his place because Bethe was better in mental arithmetic and other such calculations. Bethe could carry out an entire physics calculation in his head. When the war was over Bethe persuaded Feynman to come to Cornell where he made his great contributions to quantum electrodynamics.

While Bethe was never a technical climber he was a great mountain walker. He had discovered Aspen a few years before the Physics Center was created and had come on vacation to walk in the mountains and to listen to the music. It was natural for him to come to the new Center as a participant. When Bethe won the Nobel Prize in 1967 for his work on stellar energy he gave a portion to the Center for the construction of a new building which is now named for him. He died on March 6, 2005. Stranahan recalls that Betsy Bank came to him during Bethe’s first summer in a state of near panic. Bethe wanted to dictate a letter to her and she had no idea how to do that. Stranahan told her to fake it and apparently that worked. Stranahan was quite content with the Center’s symbiotic relationship with the Institute. People like Bethe participated in the Institute seminars which was certainly a good thing. It might have continued like that for some time except that in 1965, Craig was forced out. The new direction of the Institute could not see why they needed a Physics Division and indeed why their building could not be better used. There was a real possibility that the Center would close.

Chapter III: The 1960s

Hilbert

David Hilbert wearing a sun hat.

The Physics Center I encountered in June of 1969, my first visit, differed in several respects from the Center of 1962, its first year. Firstly there was the second building–Hilbert. This was the unheated wooden structure that had been constructed to house a group from what was then called The National Accelerator Laboratory–now the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory outside Chicago. This group had decided that Aspen would be a good place to do their planning for the new accelerator and the director, Robert Wilson, had had the structure constructed. When the study group moved on, Wilson gave the building to the Center and it was named “Hilbert.” A rakish photograph of David Hilbert wearing a sun hat hung in what passed for the lobby.

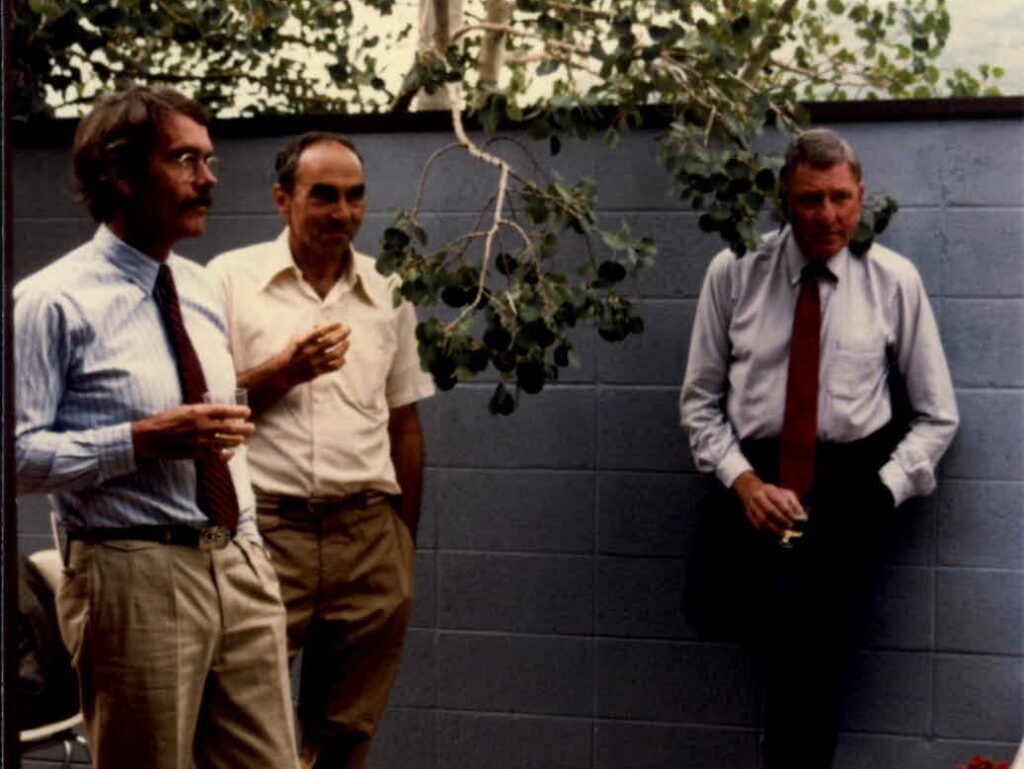

There were also changes in and around Stranahan Hall. There was now an administrative office. It was shared by Stranahan and Sally Hume Mencimer, a former school teacher, who had been hired to do the administration of what was developing into a larger enterprise. Her husband Bill had been a rancher and a ski pioneer. He had a wide mechanical skill set and took care of the four acres of grounds as well as the large fleet of bicycles which could be borrowed by the participants during their stays. Behind Stranahan a covered patio had been built. It had blackboards and could be used for the seminars which were now a permanent fixture. Indeed that summer there was a week–long workshop on pulsars which made use of the patio. There was also a volleyball court that the physicists used with a good deal of enthusiasm. But there were changes that were not visible.

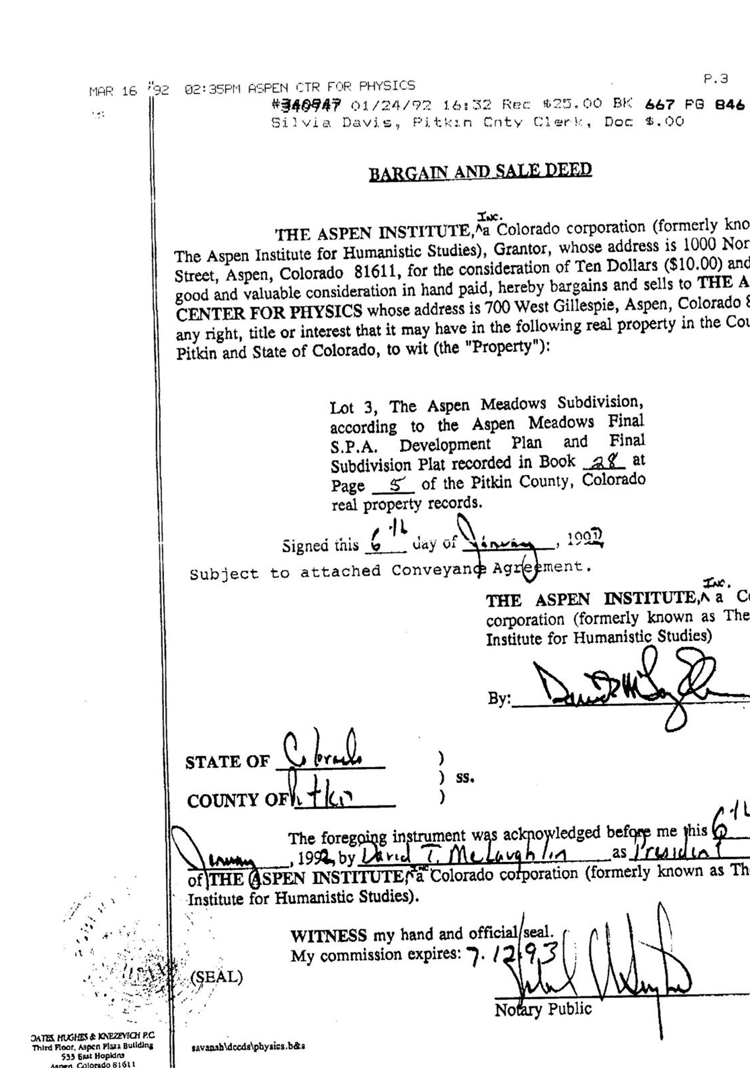

After Craig was forced out of the Institute management in 1965, the Institute severed its formal ties with the Center. They still owned the land and the buildings but now the Center was a separate 501(c)3 non–profit corporation. It was responsible for its own books and was required to have a board of trustees with given responsibilities. The non–scientific members of the board were Craig, who still had interests in Aspen, and Robert O. Anderson, the oilman whose financial backing kept the Institute afloat. Anderson was an interesting man. He had been born in Chicago in 1917. His father was an oil and gas banker. Anderson spent his summer vacations from the University of Chicago working as a pipeline maintenance worker in Texas. He then went to work for an oil company, borrowed $50,000, and bought a one third share of a refinery in New Mexico. He soon bought other refineries and in 1957 discovered the Empire–Abo–Field in southeastern New Mexico. Six years later he merged with the Atlantic Refining Company of Philadelphia which in turn became the Atlantic Richfield Company–ARCO–and Anderson became extremely rich. He also developed an Aspen connection, part of which involved Herbert Bayer.

The story goes that Anderson was walking in Aspen and he came upon an ultra-modern Bauhaus designed house, liked what he saw, and knocked on the front door and introduced himself to the house’s owner, which was Bayer who also had designed it. That began a life–long friendship. Bayer designed the ARCO logo and supervised its acquisition of the world’s largest corporate art collection. Not only did Anderson have an interest in art, but he seems to have done things like staging the performance of Shakespeare plays on his ranch in New Mexico. He was also a physically imposing figure. He could also be maddening. The one thing that the physicists wanted from him was their land. Anderson could have done this with a stroke of a pen but he kept putting the matter off. At one meeting of the Center’s Board of Trustees he lectured the physicists on the virtue of trickle–down agriculture of the kind practiced on the terraced fields of Asia. At the other end of the professional spectrum of board members was Hans Bethe who had recently won the Nobel Prize and Murray Gell–Mann who would win it that fall. I have discussed Bethe in the last chapter. Here I want to say something about Gell–Mann.

Murray Gell-Mann

He was born on September 15, 1929 in Manhattan to a family with Austro–Hungarian origins. In 1937, at the age of 8, he entered the 10th grade at the Columbia Grammar School in Manhattan, having skipped a few grades. He graduated in 1944 valedictorian of his class. I was then a sophomore at the same school but we never met until many years later although our common math teacher, James Reynolds, often referred to him as an example we could not hope to emulate. At age fifteen he was admitted to Yale where he studied physics. He applied to several places for graduate school. In some he was turned down and in others he was accepted but without the scholarship he needed. He was finally accepted at MIT to which he went with considerable reluctance. But he came under the supervision of Victor Weisskopf, a first–rate physicist and a wonderful teacher. Weisskopf recommended him to Robert Oppenheimer who was then the director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. In 1951 Gell–Mann began a stay at the Institute. It was here that his remarkable abilities began to be exhibited. While he was at MIT he had met Marvin Goldberger, “Murph,” who was there on leave from the University of Chicago. Goldberger, who was also an Aspen trustee that summer, told me that when he returned to Chicago he told Fermi, who was a professor at the University of Chicago, that he must hire Gell–Mann and he did. Fermi died in 1954 of cancer and with his death, much of the Chicago physics department left, including Gell–Mann who went to Caltech in 1955. He went in part because Feynman was there and the two of them collaborated for some years. I had the chance of working with Gell–Mann in Paris in the years 1959–1960 when he was struggling with the ideas that soon after led him to his unifying theory of elementary particles and the quark. While Bethe conferred the prestige of the older generation on the Center, Gell–Mann’s presence attracted the younger generation. Many of them timed their Aspen visits to overlap with his. He was sufficiently taken by the place to use some of his Nobel Prize money to buy a blue Victorian house in Aspen. Other visitors to the Center eventually bought places in Aspen.

The First Years

The Board of Trustees had officers. Among them was Stranahan as president and Craig and Gell–Mann as vice presidents. Michael Cohen was elected treasurer. But Sally Hume Mencimer paid the bills and kept the books. The treasurer’s report was rather simple. As of mid–summer there was $14,700 in cash in hand. Donations and grants of $25,500 had come in. The Sloan Foundation had given $20,000. There was a gift of $5,000 from Duane Stranahan, George’s father, and $500 had come from Bethe. That summer the Center would cater to close to a hundred physicists so it was a lean budget.

In addition to volleyball the principal recreation of the physicists was hiking and climbing. If you took some remote trail on a Saturday you stood a good chance of finding a physicist. During the week you might find several on the Ute Trail, an exercise trail that led part way up Aspen Mountain. The Ute Indians were the original occupants of the valley and the town was originally called Ute City until the name was changed to Aspen in 1880. Hiking and climbing were taken very seriously. A large topographical map was installed on a wall in Stranahan and by Wednesday, groups of physicists could be found studying it to plot that weekend’s adventure. There was no decent hiking or climbing guide to the area so the physicists wrote one. It contained general advice such as, “Sneakers are not at all satisfactory on snow. The terrain and trails around Aspen tend to be very rocky and boots can make even a short trip much more comfortable. Nevertheless, sneakers are very nice on day trails.” It warns against drinking water from the streams which are contaminated with Giardia very likely spread by beavers. There is a warning about lightning. “ It is not uncommon on the higher peaks and open slopes. Leave early on long climbs, and plan to be off the top by noon, when the weather is likely to move in. The best precaution is to watch the weather, turn back if lightning moves in, or if caught, take shelter in the lowest spot around. It’s no fun to be in an exposed spot.” Physicists reported that they had been in places where their ice axes buzzed when an electrical storm moved in. The guide explains the routes on simple family day hikes to climbs of some of the nearby 14,000–foot mountains.

At the end of their stays the physicists were encouraged to write brief reports. A few said that they were from remote universities and that this was the only time they were able to interact with other physicists. Many said that they were relieved to be away from the pressures of university life such as faculty meetings and deans. One gets a sense from the reports what was of special interest to physicists at the time. A few discuss things that would later turn into string theory which became a Center specialty. Bethe’s report is especially interesting, He lists his second Center stay from August 4 to September 12, 1969. He writes in part, “I attended the conference on pulsars from August 19 to 23. Many interesting papers were presented which made the present status of the subject very clear to me, who had essentially no previous knowledge of it.” He then describes some of the physics he did but notes, “On August 7, I gave a public lecture on ABM (anti–ballistic missiles ) in Paepcke Auditorium, [this was and is a large auditorium on the Institute campus] discussing why, in my opinion, ABM will not contribute to the security of the U.S.” The physicists were reaching out to the community to share their knowledge.

Chapter VI: Reaching Out

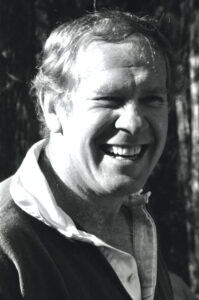

Heinz Pagels

Heinz Pagels portrait by Bernice Durand

I first met Heinz Pagels when he came to Rockefeller University in 1966 just after getting his PhD from Stanford. I was then a visiting professor at Rockefeller and I attended the first seminar he gave there. He struck me as a golden boy–handsome, very gifted and a little naïve. But I only got to know Heinz in Aspen. After my first couple of visits I developed a modus operandi. I applied to come for the month of June and then I would spend most of the rest of the summer in Europe. There were several reasons why I chose June. It was the off–season in town. The music did not begin until the end of the month. I liked the peace and quiet. It was also something like the off–season at the Center. The months of July and August were the most requested and as the Center became more and more popular they were the most difficult times to be accepted. Not too many people wanted to come in June. I also liked the snow. The high country was still snow–bound. In some of the places I hiked there were no tracks. I remember being in a high snow–bound valley and seeing a mountain lion across the way. It must have spotted me because it took off with leaps and bounds.

Heinz joined a group of us who hiked or climbed every week. He was a natural and seemed to bound along like a gazelle. Sometimes the two of us went out alone and talked endlessly about everything. It was inevitable with his genius for friendship and organizational ability that he would be asked to become part of the governance of the Center. On one of our hikes he asked me if I would also like to play a part. I said that I would and thus began a many–year role in the affairs of the Center. I eventually became a vice–president of the Physics Center and got to spend more time in Aspen. For a couple of summers Heinz and I shared an office. This brings me to the summer of 1988.

Early in the summer a group of us made a straightforward climb to a peak on the Continental Divide from which there was a spectacular view. Heinz proposed that we go down a different way from the one we had used going up. I was not enthusiastic about trying novel down routes that none of us had been on. But it looked like it might be all right. At first it was easy but then we hit a bit of nasty rock climbing and I was glad when we got back on a broad ridge. The route to the meadows below was straightforward and we were able to pick up a trail. I was walking along when suddenly I saw Heinz on the ground. Somehow his leg had given out and he had fallen. It seems at some point in his childhood he had had polio and this had left him with a weakness in his leg. I took a look at his boots and they were awful–very badly worn and bent out of shape by pronation. I commented on this and he explained how comfortable they were and he got up and loped off as before.

Drawing of routes up Pyramid Peak

We did a few more hikes and on Saturday, July 23, he told me that he was going to take his former student at Rockefeller, Seth Lloyd, up Pyramid Peak. Pyramid Peak is a high and potentially dangerous peak a few miles from Aspen. The danger lies in the loose rock which can fall on you and anyone below you and which you cannot count on for solid holds. A colleague and I had climbed Pyramid with Heinz the year before. We took the easier of the two routes, the one on the right in the drawing. At one point there is a step that takes you over the north face. It occurred to me that this was one place on the route where a fall would be absolutely fatal. Heinz wanted to take Lloyd on a traverse of the mountain going up the left–hand route, over the top and down the way we had gone up. They completed the first part of the climb and were on their way down with Pagels in the lead. At just this spot he fell. I can only imagine that his leg must have given way again. Lloyd raced down the mountain to get help but Pagels was killed in the fall.

I learned about this when Pagels’s wife, Elaine, called that afternoon to tell me. I was stunned. The only thing I could think to do was to call Sally Hume Mencimer. Not only was Sally our administrator but she was also a friend of all the physicists. She was the only person I could think of who could help in this time of grief and she did by going to Elaine and offering what comfort she could.

The news of Pagels’s death was devastating. He was only forty–nine. In addition to his wife Elaine, there were two young children. His son Mark, who had been born with a congenital heart condition, had died at age six the year before. But at the time of his death Pagels had an international reputation. He had written three very successful popular science books. The last of these, The Dreams of Reason, he had dedicated to his dead son. He had left Rockefeller to become the chief operating officer of the New York Academy of Sciences, a moribund institution which he had revived. It seemed clear that he was headed in the direction of running a great foundation or becoming the president of a university. The accident just broke your heart.

Regular Public Lectures

At the Center we debated as to the best way to honor his memory. We finally decided that given his interests in the public understanding of science the most appropriate thing would be to name a lecture series in his honor. The Center had already been giving public lectures. In Chapter III, I noted that in 1969 Bethe gave a lecture on the proposed anti–ballistic missile systems. But our lectures were not under any special rubric. The summer of Pagels’s death, before the new lecture series was organized, we had offered five public lectures on subjects that ranged from high temperature superconductivity to superstrings, the latter given by the future Nobelist David Gross. But we wanted the Pagels series, which began in 1989, to be a little different. The first lecturer in the series, which was on July 5, was Stephen Hawking.

At the Center we debated as to the best way to honor his memory. We finally decided that given his interests in the public understanding of science the most The presence of Hawking at the Center presented certain minor logistic problems. He traveled with a small retinue including an assistant and a nurse. He had a wheel chair and a voice synthesizer, which operated by spelling things out on a computer. His office was next to mine but apart from smiling I did not try to have a conversation. However, he was an icon and people with handicaps from all over the region tried to contact him. The lecture “Black Holes and Their Children, Baby Universes,” had been pre–recorded on the synthesizer. To say it was a success grossly understates the case. We could not fit the people into Paepcke Auditorium. It was filmed and made available on television. What surprised me about it was how funny he was. Of self–pity there was none.

Hawking’s lecture set a standard of public interest that was impossible to maintain. But we tried. There were some physics lectures and I gave a lecture on trekking in Bhutan. This, of course, had nothing to do with physics but I thought that it was something that Pagels would have liked. I began my lecture by telling a story about Pagels that I think showed why he was such a lovable character. My writing career had begun before his and at some point the Book of the Month Club was going to feature one of my books. I was then in Aspen. They needed a picture of me. They agreed to send a photographer from Denver. He arrived at the appointed time, about 9 am, and was sent to the office I shared with Pagels. I was not yet there so Pagels told the photographer that he was me. When I arrived Pagels was outside posing for pictures. I attempted to explain the mistake and was not helped when Pagels said to the photographer, “He has days like that.” I finally had to show my drivers license to the photographer, who was not amused.

The lectures played another role. Compared to the Institute and the music people, we kept a pretty low profile. All anyone saw were a few physics professors riding on bicycles or hiking in the mountains. Our seminars were not announced in town and were not open to the public. A couple of times a summer we gave a cocktail party to which a few of the locals were invited. That was about it for town/gown relations except for the fact that we rented a great many accommodations. The Institute also rented housing in town as did the music people, who only later would have a small campus outside of town for housing its students. The music students and faculty gave many public concerts during the summer. We had been quite content with our invisibility until it became clear that we might lose the land on which we had been operating, and we realized we were something of an unknown to many locals. Public lectures gave us visibility.

Acquiring the Land

To understand the sequence of events that ensued it is useful to refer to the geography. On the map below the Physics Center is located at Sixth and Gillespie Streets. To the north are the music tent in which concerts and special events like Stephen Hawkings’ lecture are presented, and other buildings that the Institute uses for its programs, including an auditorium. To the west is the Aspen Meadows where Institute visitors are housed. Between the Physics Center and the Meadows there is an open sward about the size of a football field, which was known as the “riding ring” or “race track.” There is a fairly wide dirt path around the perimeter of the track, which apparently was once used to ride or race horses. By the time the Center was founded it was a jogging path and a good place to walk dogs.

New activity at the Institute was to take place at the Meadows and environs. The Physics Center was not directly involved or so it seemed. In Aspen, making changes to land use is a very complex business. There is what is known as the Planning and Zoning Commission. It is a seven–member volunteer body that is appointed for four–year terms by the Aspen City Council. It recommends to the Council whether or not a land–use application should be approved. In the winters of 1978 and 1979, representatives of the Institute appeared before the Commission to present their new plans. There were to be 245 guest rooms, 18 new townhouses for Institute faculty along with the 61 townhouses and guest rooms that were already there. In addition there would be 50 employee housing units. The Institute owned 125 acres of land, which of course included the Physics Center and the music tent. These new facilities were going to be built on the 26 acres at the Meadows, which is marked in the large green area in the map below.

There were objections from the Council, to which these plans were presented, that the Institute project was too large. The Institute reduced the size. But there was one thing about which they would not compromise and that was the use of the lodging rooms. The Institute insisted that at times, some of these should be hotel rooms rented out on a transient basis to people who were not necessarily connected to their programs. The Council was equally adamant that this was not an appropriate use for an area zoned as educational. A compromise was proposed by the Council in which at any given time forty percent of the rooms could be used this way; the Institute found this unacceptable. On July 23, 1979 with a six–to–one vote, the Council turned down the Institute’s proposal. R. O. Anderson was livid. Indeed, the Institute filed a lawsuit in which individuals, past and present, whom he felt were responsible, were named. The suit alleged that the City and the Council “exceeded statutory authority and purposes and capriciously abused their discretion and violated the plaintiffs’ statutory and constitutional rights.” Anderson stated that, “This delay has been very costly to the Institute. Even beyond that, the city now proposes to take away our right to use our existing rooms at the Meadows, our own property, as we have for over a quarter of a century.”

One curious note in the suit was the complaint that the Physics Center and the Music Associates of Aspen had had master plans approved by the city without any overall plan for such an area. The music people wanted to improve their performance facility and the Center wanted at some future time to construct a new building to provide additional working space for the visiting physicists. Needless to say, since the Institute owned the land, and nothing could be constructed on it without its permission, such approval by the City was largely academic. In September Anderson announced that some of the Institutes’ programs would be moved from Aspen to a new site near Crestone, Colorado. Anderson commented that, “It is a special opportunity that is beyond the reach of our present facilities in Aspen.”

A back–and–forth continued throughout the spring of 1980. It seemed that a compromise had been reached in which the Institute agreed to rent out only forty percent of its rooms at any time for transient use. But on June 19 the Aspen Times reported a rumor, which was confirmed a few days later, that all the Institute property in Aspen had been sold to a local developer named Hans Cantrup. He had an interesting history. He was born in Berlin, Germany in 1929 and in 1950 came as an exchange student to Syracuse University where he studied business administration. In 1954 he came to Aspen to ski and paid for his lift tickets by waiting tables at a local restaurant. He decided that Aspen had a future as a tourist destination but that it lacked accommodations. No bank would lend him any money to build lodging, so he borrowed enough from some ranchers to build the fourteen–room Smuggler Motel in 1955. By 1980 he was the largest landowner in Aspen with properties all over town. In the fall of 1979 he paid $2 million in cash to buy 300 acres of mining claims at the base of Aspen Mountain. He had no intention of looking for silver but rather wanted to build a luxury hotel. At the present time there is a string of luxury hotels at the base of Aspen Mountain, but at the time it was largely open space. Cantrup had a soft spot for music students who came to Aspen in the summer and rented places for them to live at less than the going rates.

What Cantrup actually bought was all the shares in something called the Meadows Corporation, a subsidiary of the Institute since 1977. He paid $5 million for the shares and assumed a $900,000 debt. The Institute had been running at an annual deficit which was as high as $750,000 and for 24 years Anderson had been covering it and had now stopped. In addition to these payments, Cantrup assumed a debt of $3 million which had to be paid back in five years, otherwise the property was to be returned to the Institute. As we shall see, this is what happened. But in this moment of euphoria, Cantrup said he would give the Music Associates the land they needed. Of the Physics Center nothing was mentioned. Most of the physicists that summer had no idea of what was happening. One of the topics they were discussing was quasars. By this time astronomy had arrived in full force at the Center.

Chapter V: The Circle of Serenity

Real Estate Fiasco

While Cantrup was well–known in the Aspen community the next player was completely unknown. His name was Mohamed Hadid. To produce a detailed biography is a challenge since he always enjoyed a certain air of mystery. From what I have been able to piece together he was born in Nazareth, Palestine in 1948. His father taught English at the University of Jerusalem. When he was two months old his mother took him to stay with her mother in Damascus. When they returned they found the house empty and his father gone. The state of Israel had been created and they were refugees. According to Hadid his mother loaded him and her other possessions on a donkey and they walked back to Damascus. They assumed that Hadid’s father had died. But after almost two years he turned up in Damascus and the family was reunited. He found work at the United States Information Service whose offices were transferred to Tunis where Hadid and his seven brothers and sisters spent the next ten years. But in 1964 Hadid’s father got a job at the Voice of America in Washington and the family moved to northern Virginia where Hadid went to high school. His college education, if any, is rather murky. He did not get diplomas from the schools he claimed to have been enrolled in. He seems to have run a nightclub on the island of Rhodes and then he opened an imported car dealership named the Georgetown Classic Motor Corporation in Washington. This was followed in 1978 by the creation of a company called American Export and Development Company which exported construction equipment to Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar. At the time many wealthy Arabs wanted to invest in real estate in the United States and Hadid and a partner opened a real estate firm, Oasis Development. Their first venture was an office building in Washington which was purchased with money from an investor in Qatar. This led to a variety of such transactions and in 1987 he became associated with the Saar Foundation. This was an entity founded by a Saudi that theoretically used the proceeds from its investments to fund various good works in the Middle East. In 1986 Hadid began doing real estate investing for the Foundation. In 1987 the Foundation decided that too many of its investments were in Washington and asked Hadid to look elsewhere. One of his associates was a lawyer named Alan Novak who had Aspen connections. It was he who clued Hadid in to the prospects at the base of Aspen Mountain.

The sequence of steps that led from Cantrup to Hadid were about as complex as the quantum mechanical measurement paradox. They would not be worth our while here except that without these steps the Physics Center might never have acquired its land. This was potentially very serious. By the 1980’s the Center had become one of the foremost research facilities in the world for doing summer physics. It had grants from places like the National Science Foundation and NASA. It had had visits by Nobel Prize winners such as Richard Feynman and Philip Anderson. There was a long waiting list each year of people who had not been accepted. In short it was a success beyond the founders’ dreams. Yet it was on thin ice. Despite several attempts, there was no document from the Institute that the Center had any right to be there. Now, even if there had been such a document, it was not at all clear what it would have been worth. The situation was precarious. The Center desperately needed its land.

The events that eventually led to acquiring the land began in March of 1983 when Cantrup and his wife declared bankruptcy and the 26 acres at the Meadows were returned to the Institute. This did not come as a big surprise. He had so many balls in the air at any given time that it seemed inevitable that he would drop a few. His debts were estimated at some $40 million. There was a Texas entrepreneur named John Roberts who was the head of something called the American Century Corporation in Dallas. He also had control of the Commerce Savings Association of San Antonio which lent him $42.9 million to buy the Cantrup assets. But nothing was simple and it took until January of 1985 before Roberts could actually buy the property. That May the City Council approved the plans for the hotel at the base of Aspen Mountain. But then Roberts went broke and a foreclosure proceeding was begun by Commerce Savings to regain its assets. While this was still in process, in February of 1986, Donald Trump bought the land at the base of Aspen Mountain, or so he thought.

Trump decided not to pay for his purchase until the Roberts–Commerce foreclosure proceedings were actually complete. This left a loophole. Roberts had a fixed amount of time to find another white knight, one who might take Cantrup’s Institute assets off his hands. Trump had no interest in these. He wanted to build a hotel. He was so confident that no such white knight would be found that he actually hired a local architect to begin designing the hotel and in a gesture of good will offered to build the town an ice skating rink. The aforementioned Alan Novak, who had also been associated with Roberts, apprised Hadid of this opening. Hadid raised $42.9 million from his Mid–Eastern sources and bought the whole parcel of land from Commerce. Not only had he purchased what he thought was an excellent piece of land but he had the satisfaction of having beaten Trump out. This happened on the 26th of June. The following January the two men and their representatives met at the Waldorf Astoria in New York for lunch. Reports are that it was a “love fest” at which the two men talked of future mutual plans. Sometime after the lunch Trump sued Hadid. But this left in the air what Hadid planned to do with the Institute land which he now owned.

The company that Hadid set up for his Aspen transactions was called the Savanah Company and one of its associates was a man called John Sarpa. Sarpa had gotten his undergraduate degree from Indiana University and his law degree from the George Washington National Law Center. He was interested in the Middle East and had learned Arabic. While still in his twenties, he became Director of Middle East Affairs for the United States Chamber of Commerce. In this capacity he became part of President Carter’s delegation, which negotiated the peace treaty between Menachim Begin and Anwar Sadat. One of his tasks with Hadid was to represent Hadid to the Aspen community. This was going to take some doing because it appeared as if Hadid wanted to use the open space by the Physics Center and land abutting the music tent for some kind of residential development. Sarpa tried to be reassuring by noting of Hadid that, “The environment is something he is very much in tune with and appreciates.” The image being presented was that when Hadid was not at one of his development sites he was tending his garden. Sometime after the purchase, representatives of the Institute, the Music Associates, the Design Conference, which held an international conference on the Institute’s grounds in the late spring, and the Physics Center were invited to meet Sarpa. Since I was then a vice president of the Board of Trustees I was one of the representatives at the meeting.

Sarpa walked into the meeting carrying a book. One had the impression that this was his first visit to Aspen – he now lives there – and the book, which he said he read on the plane, explained the “Aspen Idea.” As far as I knew the “Aspen Idea” was something that Walter Paepcke had in mind when he founded the Aspen Institute. Captains of industry would have the opportunity of learning about Greek philosophy in the morning from people like Mortimer Adler and in the afternoon go for hikes in the mountains. It was not clear what it had to do with the case at hand. Sarpa then produced a drawing of Hadid’s vision for the land. The open space, which at that time was a prairie of native grasses and wild flowers, was to be replaced with what looked like a small village of houses. In the middle there was a taller structure which seemed to be a future hotel. I think that it is fair to say that the representatives of the non–profits, including myself, were appalled. It looked like the makings of a disaster. We all felt that the only thing that could save us from this folly was the Aspen City Council whose approval was necessary.

The Circle of Serenity

Up to this point the Center had not been much involved with local politics partly because we were a summer institution whose participants went back to their universities once the summer was over. A few people like Stranahan were around during more than the summer but that was about it. It was clear that now we had to make our case to the community. At this point the physicist Elihu Abrahams came up with an idea of genius – the notion of the “circle of serenity.” This was an imaginary and somewhat irregular circle with its center at our buildings. It encompassed to the north the volleyball court on which the more athletic physicists and their families played spirited games. To the east was the Boettcher Seminar Building which was part of the Institute complex. To the west was the racetrack and to the south was our front lawn with a large bicycle rack that contained the bicycles that the Center loaned to the participants and their families. This whole circle was our “circle of serenity” and all we were asking was to preserve it for the Center’s use.

A Schematic Map of the Entire Area Showing at the Bottom the “Circle of Serenity”

It was a very successful rubric, which even made its way into the local media. The image was of these physics professors unlocking the secrets of nature in this harmonious preserve.

A practical effect was that the Center became part of a “consortium” of users of what became known as the “academic campus.” It excluded Hadid and consisted of the four non–profits, the Aspen Institute, the Music Associates, the Physics Center and the International Design Conference, which played a small role only at the beginning. It was understood that any arrangement for the land had to serve the needs of the consortium jointly. This was very important for the Center because if viewed objectively, we brought relatively little to the table as compared to the Institute or the Music Associates and now we had something like an equal vote. Peter Kaus, who had been president of the Center, had created a Planning Committee of which Stranahan was spokesperson and Kaus was chairman. One of the things that Kaus did was to fend off a suggestion that the Center move its operations to a less valuable piece of land somewhere else in Aspen. For the next few years various proposals were floated. It was suggested that the community should buy the academic campus and turn it over to the non–profits. This got nowhere. There was the suggestion that some of the land should be used to build a new elementary school. This also got nowhere. Elizabeth Paepcke, Walter Paepcke’s widow, told the Aspen Times that, “The only person we can rely on with hope is Mister Hadid. Please trust Mister Hadid.” “Mister” Hadid was having his hands full with his hotel at the base of Aspen Mountain – a Ritz–Carlton. The Council approved its construction but then that approval was declared illegal. Finally it was decided to put the matter to a city–wide vote which Hadid won. In November of 1989 Sarpa told the Council that, referring to the academic campus, which Hadid still owned, “We have no goals for the property outside those of the non–profits.” The idea of a little village on the academic campus had apparently been abandoned. Hadid simply wanted permission to build enough houses somewhere near the Institute so he could break even on his investment.

“We have no goals for the property outside those of the non–profits.”