Letter from the President, 1983-1985

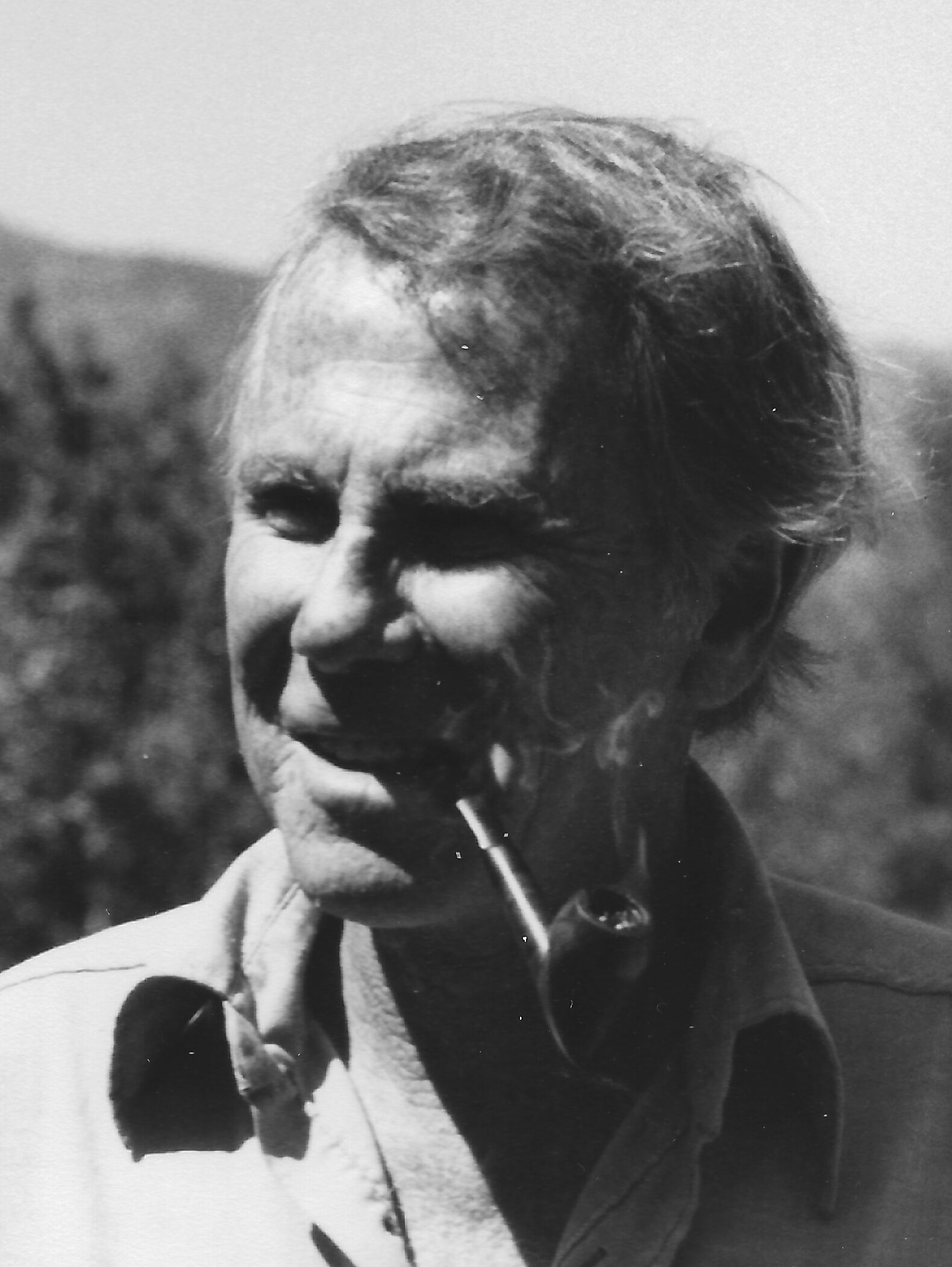

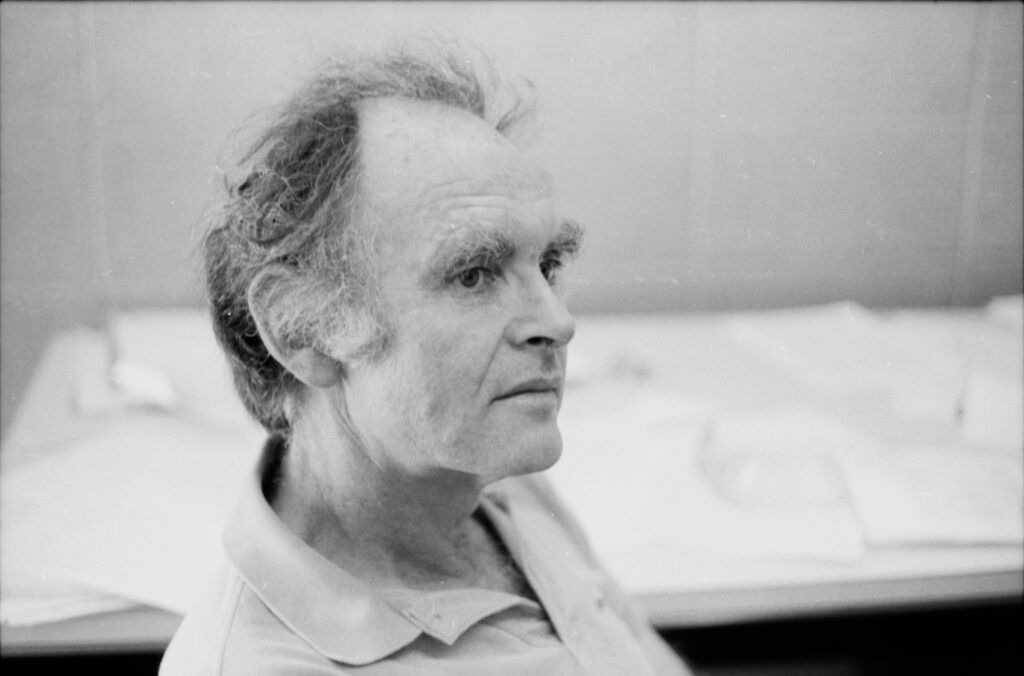

In 1956 I found myself in Princeton. I was simultaneously at RCA Laboratories, designing the deflection yoke for the first commercially successful (21 inch) color TV tube (my first salaried job) and at the Institute for Advanced Study as an (unpaid) scholar finishing my thesis work on self composite fermions (Solitons). An RCA friend came to my office one day to tell me that a biologist, Colin Pittendrigh, who was doing most interesting work in biologic clocks (later named by him circadian rhythms), needed mathematical help to put his model into quantitative predictive form. I jumped at this opportunity and became a lifelong dilettante member of his Princeton, later Stanford, team. I now had three jobs in three different fields and institutions. 1958 was my last year in Princeton, mostly consumed by looking for an academic position. Why do I bother to tell you all this? It is because it is at this time that the non–existent Aspen Center for Physics became part of my subconscious mind.

The occasion was an evening at David and Suzy Pines’ home with the Pittendrighs, who talked in glowing terms of summers they had spent at a biology research center in Gothic, a ghost town in Colorado, a day’s walk from Aspen over either East or West Maroon Pass. Four years later I was working with Fred Zachariasen at his office at CalTech. (We had one day a week reserved for this either at my office at UC Riverside or Fred’s office in Pasadena.) Fred opened a letter from Mike Cohen, a roommate when they were both graduate students in Pasadena. It was an invitation to be a charter participant at a research center which would open in 1962, in an area of great beauty. It was to be called “the Physics Division of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies” mainly as a place to do “your own thing” away from the bother of the home institution in the company of the best. There wouldn’t even be seminars. Just conversation for those that wanted it.

Fred couldn’t go that summer. He showed me Mike’s letter and the beginning of his reply which was so insulting that I was sure he and Cohen were bitter enemies. In fact they were good friends and this was the tone of their most amicable conversations. I told Fred that I wanted very much to go and would he please include that in his answer. Fred’s letter is in the ACP archives and does indeed include me. Ending with “ ….he is not totally stupid…. ” not much of a recommendation, but it was enough to change my life. I was invited and now have attended 50 times.

The First Twenty Years 1962–1982

We had been warned to expect rustic quarters. When we arrived in Aspen, however, we were directed to a luxurious small modern house in the “prestigious” West End of town. The kitchen was furnished with many glasses, but not too much cooking equipment. The Center would be a few blocks away, 6th Street and Gillespie. To the North was an empty field with the first building of the Center in progress but by no means finished. The building, (Stranahan) consisted basically of ten offices for two, which allowed for twenty participants, and a reception space as well as a small, pleasant room which could accommodate the participants for seminars. We were given work space by the Aspen Meadows Hotel for several weeks in very nice hotel rooms, so we could start whatever we wanted, while “Stranahan” was being finished. We soon met Mike Cohen, George Stranahan, and Bob Craig; our founders. It turned out Mike and I had both been at the “Institute for Numerical Analysis” for a while in the fifties and knew each other slightly. Craig was President of the Institute, and adding the Physics Division soon cost him his job. Stranahan and Cohen happily proceeded to organize and the Physics Division rapidly became the foremost institution of its kind, (whatever “its kind” is). I only knew that it is my home and I did everything in my power to become part of it.

An integral part of the experience was the two weekend hikes or climbs. On Saturday there was a moderate hike, organized by Randy Durand, which included children and would go to nearby passes or lakes: Buckskin, Electric, West Maroon Pass, East Maroon Pass, Cathedral, Willow, Blue Lakes. They were by no means trivial, but children as young as four often joined and many came to love the mountains. On Sunday there was often a serious climb. Mike Cohen was an avid climber and I foolishly accepted an invitation by him to climb North Maroon Bells. (Real climbers do North Maroon traverse to South Maroon and descend). I survived but knew immediately that I was not a climber.

In 1964 Sally Hume Mencimer became our secretary and soon handled most purely administrative jobs. In particular she found comfortable housing for all the participants at prices we could afford. The Center was landlord for the summer, but charged all participants the same rent according to the number of bedrooms, even though the cost to us varied and went up considerably from year to year. We were able to subsidize the participants, particularly those on a nine–month salary. In any case, the summer in Aspen miraculously was a good deal for all. This would not have been possible but for Sally’s tireless effort and success in finding bargains.

Presidency 1983–1986

I will not dwell here on the stuff in the yearly President’s Report for the Trustee meetings, but proceed to events that many of our participants were not fully aware of, but which were crucial for the existence of the Center. These were precipitated by the 1980 sale to Hans Cantrup of the Institute property on which we were situated. In 1985 I appointed the Campus Planning Committee. The committee was charged with coordinating all activities related to our campus and its surroundings. We proceeded to plan for a turf we didn’t have and surroundings we didn’t control. In fact our very existence was dubious at this time. As an organization we were arguably the most successful theoretical physics center in the world, but in terms of property we didn’t or at least shouldn’t exist in the minds of some. Let me explain.

We started as the Physics Division of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies with the first building, Stranahan, on Institute grounds. This was followed by Hilbert Hall to accommodate a study group from the future Fermi Lab near Chicago. The third building was Bethe, which housed our library, six more offices and a large room, still suitable for seminars and yearly Trustees’ meetings. All this was squarely on the land called the Aspen Meadows, 125 or thereabout acres of incredibly expensive real estate belonging to the Institute. We had separated from the Institute and were the Aspen Center for Physics, but still on Institute land. The only formal document I can find is a 99–year lease for a yearly rent of one dollar. In 1980 the Institute property was sold to Hans Cantrup, a local developer. R.O. Anderson, Board Chair of the Aspen Institute, was outraged that the City did not approve his plans for increased facilities. This was a terrible shock and probably the end of our Physics Center. We were tenants on Cantrup’s land now and he had big plans. We had some disagreements with the Institute for Humanistic Studies, but now they seemed very small.

Every president in the 1980’s had the dream that during his tenure the Physics Center would get a deed to “our” land, whatever “our” land is. Anderson implied now and then that it was indeed his intention to make us masters of our own fate. He never implied that he would sell us to a developer. What saved us is a miracle. The whole area was zoned SPA (Specially Planned Area), which meant it essentially had no zoning at all. There is a huge gap between ownership and a building permit. That is up to the City Council. That is what R.O. Anderson had found out for the Institute and now he had passed it on to Cantrup, who was the first of what would be a string of buyers with plans of many (40–60) properties. The Physics Center is situated on a big field. To the west, about ten feet lower than the Center property, is a beautiful wild meadow about the size of a racetrack. In fact we call it the race track, because it was generally believed that horse races were run on it a hundred years ago. Until now it provided a clear view off to the west, across the racetrack, down the Roaring Fork Valley with the Aspen Meadows Hotel resort barely visible.

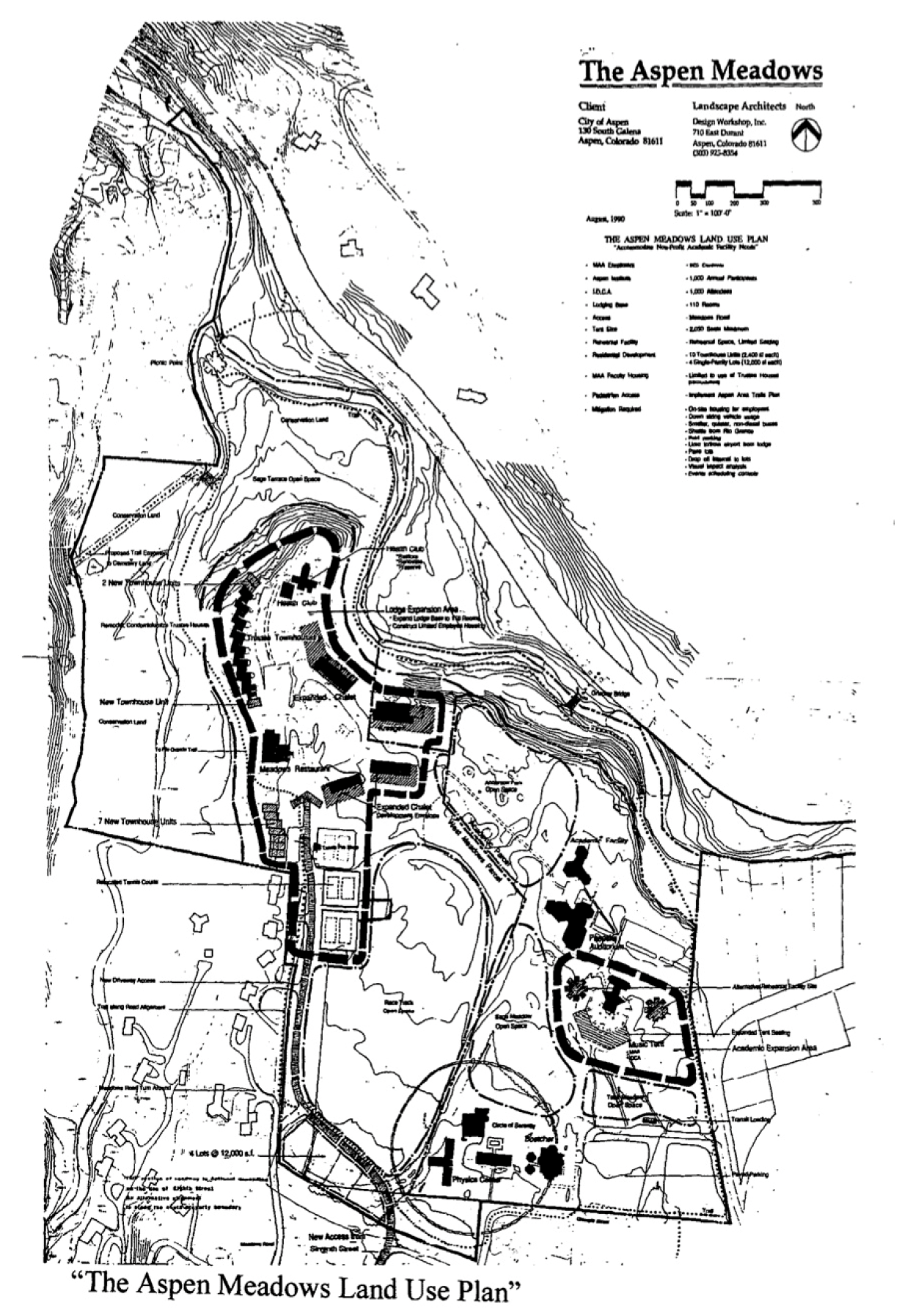

The City – Bill Sterling was mayor – saw the stalemate as an opportunity to make a comprehensive plan for the whole area. The starting evidence was the formation of the so–called “Blue Ribbon Committee.” Our representative was Elihu Abrahams, who was President of the Center at the time (1981). This was the first time that various interests were defined. (See map below).

The Aspen Meadows Resort and the race track are to the west and The Institute, the Music Tent and the Physics Center lie to the east. Elihu had discussed with me that all the other groups, but not the Physics Center, had a definite want: another seminar room, a rehearsal room for the musicians, more hotel rooms for the resort, etc. We had no land so we couldn’t want a building. Elihu came up with a brilliant answer: we wanted only a “Circle of Serenity.”

This was an instant hit. It immediately made the Physics Center a complete chess piece, with ground and borders to be defended, whether they existed or not. Above is one of several conceptual maps during the planning period around 1984. The boundaries are mostly in the mind of the planner and were in fact the subject of discussion, but this one is remarkably close to the ultimate solution. Note the “Circle of Serenity.” Also note that this map shows boundaries around four areas, with no structures, designated as open space. We were no longer an insignificant black dot, ruining the hopes of all aspirant developers to build many units in and around our Circle of Serenity, but a major player to be integrated into the East Meadows which became known as the Academic Campus and was populated by organizations called the “Non Profits.” One problem for the buyer was vehicle access to the racetrack. We knew that if there was any housing development that is where most of the houses would be. The only possibility seemed to be an extension of Gillespie, which would cut through the bottom part of our Circle.

I was approached by the Institute about the possibility of simply giving up the present Physics Center, serenity and all, and the Institute would build us a new Center further North in what is now called “Anderson Park.” I rejected this out of hand, because I was convinced that the destruction of the Physics Center would happen, but the new Center would never come about. We wanted the Center just where it is. Personally, I was getting cold feet. Irreversible decisions had to be made and there were several other suggestions around. We needed to bargain with one voice (unfortunately mine), but I was out of my depth. Then I had a great idea. George Stranahan had essentially changed his interest from founding a world-class Physics Center to pursuing cattle breeding on his ranch in Woody Creek. Without much hope, I called him and asked him whether I could persuade him to head the Planning Committee. To my surprise and relief he accepted. Having thus successfully passed the buck on matters such as trading in the Physics Center, I turned back to other matters of immediate concern. There were many meetings at City Hall and we had to be represented. Most of these were attended by Jeremy Bernstein as Vice President of the Physics Center. This was very important, because the City meetings went on after the Center had finished the summer program.

While the presidency was changing (I will never understand who is President or Vice President in November of a year of change) neither I (old) nor Mike Simmons (new) was in Aspen continuously, but I had stayed on to enjoy the fall. This is very different now (2011); just the physicist property owners of Pearl Court and The Gant condominiums, who are members and officers of the ACP could provide a quorum for many meetings. The Aspen Meadows went through several ownerships, or near ownerships, starting with Cantrup’s, who went bankrupt, continuing to John Roberts, a Dallas entrepreneur, to Donald Trump, whose interest was in building a hotel at the base of Aspen Mountain on land which was once another of Cantrup’s assets. The Aspen Meadows and the various Non–Profits were of little interest to him. Then to everyone’s surprise, both properties were snatched up by Mohamed Hadid for 43 million dollars.

Now the scene was changed completely. Hadid had to ask the city for zoning for both areas: the Aspen Meadows and the area at the base of Aspen Mountain where the huge hotel was to be. In the fall of 1986, Hadid wanted to meet the President of the Center. I managed to reach Mike Simmons, who would replace me the next summer and he came to Aspen for a few days. The interview gave us both chills. Hadid was very friendly and instead of telling us what horrors he may have in mind, told us that he had looked over all the institutions he now owned and decided that the Physics Center was by far the most important and ended with, “What can I do for you?” I assured him that he could do nothing. This was not the right answer and we left very troubled.

We weighed our power and came to a most surprising solution. The Meadows property was the home of various groups. The Center with the “Circle of Serenity” was on the south–western edge of the part of the Meadows called the East Meadows, somewhat synonymous with the “academic campus.” To the west is the racetrack and to the south is town. The inhabitants of town (of which I am one) valued the racetrack, which has a path for jogging and dog walking around its perimeter. In the early days it was also much used for horseback riding. The only reasonable access is around either the northern or southern edge of the Center. We have always maintained a path for everyone on both sides and it was much used by townies. In addition, in our quest to be good citizens, the Center also gave public lectures whenever we had a good candidate. These were given at the downtown Wheeler Opera House. They were a great success and were, in fact, the first time many Aspenites had heard of the ACP. I sponsored a “College Advisory” service, meant for high school seniors contemplating higher education. We had professors from most major universities and many were advisers at their institutions. This was not meant for future physicists, but for local kids who did not know how to go about choosing a college, preparing and applying. These small gestures made us much more part of town.

We had some good allies at the hearings. The Non–Profits, Music Associates, Design Conference and the town itself. The combination came to be called the Consortium. Hadid had several plans. One plan was for many houses on the racetrack with a little village on the academic campus. We were determined to keep the racetrack the natural prairie it was and the academic campus with as much open space as possible. Luckily, Hadid was building his big hotel, the Ritz–Carlton and had to deal with the City about that as well. He was aware that the Consortium was united against development and he started to make concessions. Eventually he was satisfied with four houses at the southern edge of the racetrack with the rest of the whole Aspen Meadows land, open–space areas and all, basically intact. We were saved. As far as ownership was concerned, nothing had changed. Marvin Goldberger, “Murph,” was a good friend, and had been at some time Chairman of the Board of the Physics Center.

At this particular time, however, he was on the board of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, which had its Trustees meetings in the fall. Before going to these meetings, he would call me and ask, if I had anything special I wanted him to convey to R.O. Anderson and I would suggest, “Let my people go.” One time Murph called after coming back from Aspen to tell me that he had a short dialogue in a taxi ride with R.O., whose answer was, “It is not convenient just now.”

It would not be convenient for five more years.

I ceased being President in 1986, feeling that the best I had done was to not be in the way and to tie the Physics Center more to the town. In the summer of 1985, my last full year as president, Marty Block who has a lovely home in town, very close to ours and the Center, talked to me about the idea of winter conferences in Aspen. There were a few such in Europe. I had attended one in Schladming, Austria, but there were none in the U.S. The proposed meetings would be one–week concentrated conferences on major timely subjects, discussing the results and implications of recent experiments. This was not a proposal for a boondoggle, but hard work. The schedule would be three hours of lectures in the morning, while the snow is still icy, followed by a five–hour ski and lunch break and three hours of lectures in the evening and finally dinner at the Meadows. I proposed to Marty that it would not be wise to create an instant tradition, but try it as an experiment and see how it went.

The experiment was a big success. The Center provided some logistic support, but Marty handled the program, the accommodations at the Aspen Meadows hotel, the ski races, which most of us participated in, at the Highlands and the banquet. Some tension occurred, because it was the first winter meeting and it was not entirely worked out what had to be done by the Center administration and what by Marty, but with some improvising we worked it out. It was clear that the Winter Conference should become an integral part of the Physics Center yearly program. This was worked out in the following year and two years ago (2010) we celebrated the Winter Conference 25th Anniversary.

In the years after 1986 the Planning Committee morphed into a two-task entity. Strategy, that is actually obtaining land to plan for, was quietly handled by George Stranahan and Turf, as the committee was called, also started thinking about the facilities if they should ever come about. Then, on March 23, 1992 we received a letter from Mike Turner “Dear Trustee/Member: I have some very good news to report: The Aspen Center for Physics now has title to about 4.25 acres of prime Aspen real estate ….. Michael S. Turner” We existed.

In fact, we owed money: $100,000 for our shares of the Meadows Plan, as well as improvements to the Meadows that must be shared by all members of the Consortium and $226,000 for a sewer hook up and other infrastructure and fees. Now it was time for the Turf Committee to create the campus you see today.