IN MEMORIAM

Nicholas DeWolf

This memorial obituary was written by Chad Abraham and published in The Aspen Times (2006) here.

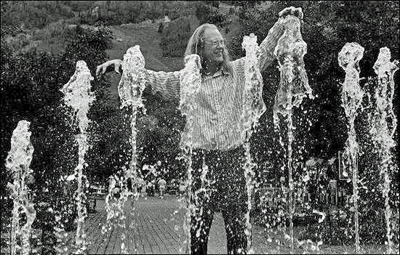

Nicholas DeWolf, an extraordinary and exuberant spirit of Aspen whose work in the semiconductor field paved the way for today’s computer industry, died Sunday morning at Aspen Valley Hospital. DeWolf, who helped create the famed dancing fountain on the Hyman Avenue mall, was 77. The cause was complications from a recent stroke and prostate cancer. “Nick DeWolf cannot be described, only experienced,” says the opening line of a section about him on an Eris Society website. He spoke before the loose-knit, philosophical consortium in 2004. “Eris gatherings are opportunities to meet some of the most interesting people in the world,” the website says. “They are a broad spectrum of individuals who have distinguished themselves in their fields: film producers, doctors, scientists of all persuasions, historians, artists, philosophers, educators, multimillionaires and hobos (at least one anyway). All are in regular attendance.” DeWolf fit nearly all of those descriptions, although he would have likely cringed at being called a scientist. He was an engineer, he emphasized in Greg Poschman’s induction video for the Aspen Hall of Fame, “not a scientist.” But he was also a husband, father, actor, inventor, photographer and a sensualist; an animal lover who was loved by animals, a provocateur, skier, and an eccentric whose office suffered, or benefited from, legendary disorganization. DeWolf, those close to him say, fought hard for Aspen’s preservation as the perfect world for providing absolute freedom of the discussion of ideas and the ability to mingle across classes, dishwashers to debutantes, Hollywood stars to ski bums. Aspen, in fact, was just what DeWolf wanted when he left the East.

Machine guns and semiconductors: He was a prodigy who was born to aristocratic parents in Philadelphia in 1928.”They were a little confused,” his daughter, Nicole DeWolf, said of her grandparents. “It is hard to get a handle on this man. He’s done so much for so long.”He graduated from Promfet Boarding School when he was 15 and earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when he was 19. DeWolf then went to work as an engineer for General Electric in the late 1940s. While there, “I tested machine guns. I managed to almost destroy a $2 million power transformer,” he said in an interview for an industry award. He was eventually lured to another company working on semiconductor prototypes, and then founded his own company with Alex d’Arbeloff. They met at MIT “when they lined up alphabetically in an ROTC class,” says a company website.The duo wanted to create a new type of industrial-grade electronic testing equipment. They rented space above a hot-dog stand in Boston and called their company Teradyne.” The new venture had to have a ‘D’ in it,” DeWolf says on the website. “‘Tera’ is the prefix for 10 to the 12th power, and ‘dyne’ is a unit of force. To us, the name meant rolling a 15,000-ton boulder uphill.”At Teradyne, where he was CEO for 10 years, engineers specialized in test equipment for semiconductors. The company’s equipment sparked an entire industry of pre-computer testing.” The transistor revolution and computerizing, all that stuff, was totally dependent on finding a semiconductor,” Nicole DeWolf said. “And they did some trippy things that no one had even thought of doing before. And it’s what makes the world as we know it. So that’s pretty intense.”

He grew weary of the corporate life, so he retired. After a year-long trip through Asia, DeWolf and his wife, Maggie, packed up their six kids and landed in Aspen. He told Poschman that he wanted to be a man without a past here. DeWolf “didn’t really want anyone to know what I had done. I wanted to earn people’s respect and a place in the community by what I did and what I was, not what I had been.” Nicole DeWolf said her father “was one of the most forward-looking people I’ve ever known. He never looked back if he could avoid it.” DeWolf’s early days in Aspen were painful, as he broke his leg in the mid-1950s on Ruthie’s Run. “The bone was sticking out of the pants,” Nicole DeWolf said. The nuts and bolts installed in his leg at the time remained for the rest of his life, and “he used to make a joke that the metal in the bone drew him back like a magnet to Aspen.” But what he loved about Aspen “is sadly what had changed about Aspen today,” she said.

Nick DeWolf and fountain.

Water and fire: Travis Fulton, a local sculptor, and DeWolf both had an idea for the components that would make up Aspen’s dancing fountain. The apparatus was completed in 1979. A computer and software DeWolf built from scratch sets the fountain’s pattern. “It’s done everything it was supposed to do,” DeWolf told the Times in on the 25th anniversary of the fountain’s inception, in 2004. “I’ve been well-rewarded by the thanks from parents and kids.” It’s not a fountain, it’s a symphony.” DeWolf the eccentric was also introduced to the Burning Man festival, a gathering of 30,000 or so people who shun society’s norms for a week in the Nevada desert. Artistic contraptions of staggering scales move about the gathering, a scene that fit perfectly with DeWolf.” His interest in Burning Man was fairly recent. But he became extremely tight with David Best,” a renowned artist and a founder of the festival, Nicole DeWolf said. ”His spirit is very Burning Man,” she said. “Unorthodox, a little racy, ideas, ideas, ideas. ”Two years ago, Best let DeWolf light the event’s Festival of Atonement, which was “a huge honor,” said another daughter, Vanessa DeWolf. For the 2002 Burning Man, DeWolf created a 30-foot-long mobile movie theater atop a recreation of a woolly mammoth. ”It had this platform you could jump on and jump off of and dance and perform. It was just this fun, crazy idea,” Nicole said.

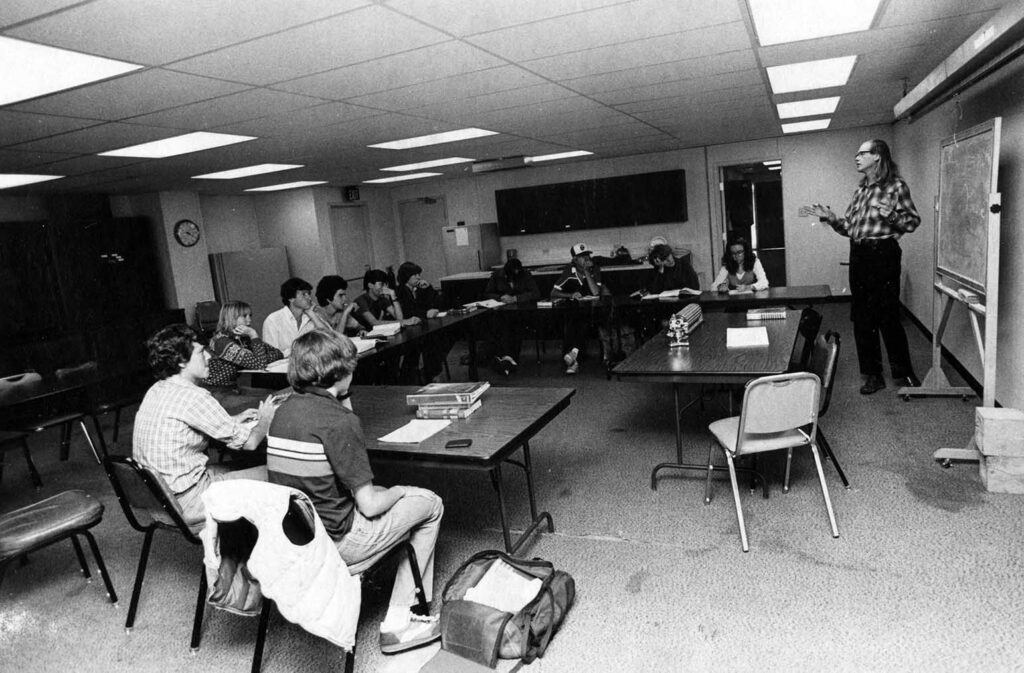

The teacher: DeWolf was an honorary member of the Aspen Center for Physics and an optimist about the powers of science. He also founded Rofintug, a local Internet service provider. “He was convinced that we all would fall in love with science, with understanding how the world works and how the air works, if only we could understand it,” Nicole said. At one point, he, Sandy Munro and George Stranahan decided to take over the physics program at Aspen High because they felt the subject was not being taught in a way to interest teens. Stranahan remembered some resistance from school officials to the threesome’s activities” The school said, ‘Well, you guys aren’t teachers, so we’re not going to give the kids credit,’” he said. “To our delight, not a single kid dropped out just because they weren’t going to give credit.”

One photograph of Nick DeWolf teaching a Physics class at Aspen High School, 1981. There are eleven students in the classroom. The photo can be found in the October 22, 1981 Aspen Times, p. 11B. This photo is courtesy of Aspen Historical Society.

The longtime Woody Creeker said DeWolf had an uncanny ability to find an obscure electronic part amid the piles of his workspace. He also knew plenty of “techno tricks,” Stranahan said. “I think he was the first one to know how to steal anybody’s e-mail address,” he said. He had that exploring mind: Let’s see if I can figure this out. And then he would.” DeWolf is survived by his wife, Maggie; six children, Alexander, Nicole, Quentin, Vanessa, Thalia and Ivan; seven grandchildren and a sister, Lucretia Hosmer. Nicole DeWolf said her father instilled in his children “complete, unmitigated love for life. And people, my dad was devoted to people. What really moved him about this place were the people.”

Positions Held

Trustee, 1983 – 1990

General Member, 1983 – 2003

Honorary Member, 2003 – 2006